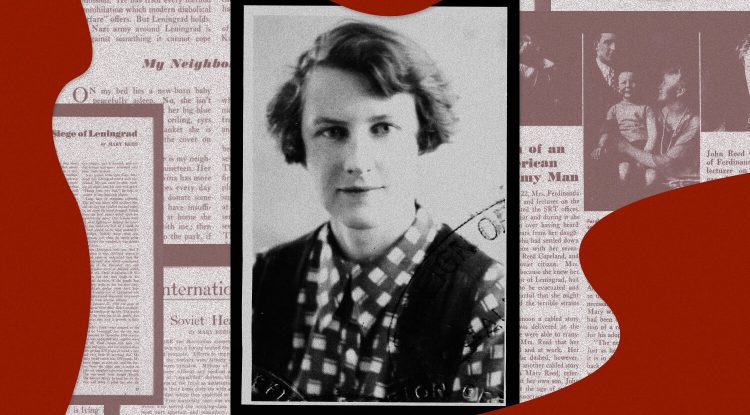

In 1927, an American socialist, journalist and poetess Mary Reed arrived in the country she had been dreaming about—the USSR. There she got a job at the Comintern, met her future husband, survived the Siege of Leningrad, lost her only son and was sent to the Gulag following her letter to Stalin. No one knows her name in the US, and barely anyone noticed her presence in Russia. Read her story put together by Holod.

“...[the policemen] jumped out with guns aimed at us, yelling. They snatched the banners, grabbed as many people as they could get hold of and forced them into the police patrol. When the patrol was full they turned on us with their guns and began firing. We retreated. Some fell and lay bleeding, others carried them off. Others threw stones at the police and we moved ahead again. Then they shot us back, and there were more wounded...”

This is how Mary Reed described the International Workers’ Day demonstration that took place in Boston on May 1, 1919. Or rather, it didn’t: the procession was dispersed. A 21-year-old college student, Mary encountered such bloodshed for the first time, but by then she was no longer surprised by the police’ actions. Reed, who was a law student at a women’s college in Boston, regularly traveled to a neighboring town to support textile workers’ strikes: every day at 6 am they began pickets demanding an eight-hour workday, while mounted police beat them with batons and detained them.

These events made a lasting impression on Reed. She became convinced that “ [the] Great American democracy has all leaked out [of the chest where it was contained].” She learned of the place where the true power of the people was championed some time later, from her namesake, John Reed, a left-leaning journalist who had been in Russia during the October Revolution and had written a book about it, Ten Days That Shook the World. After listening to Reed giving a lecture on Soviet Russia, Mary decided: “As for the Russian Revolution, I now supported it without reservations. Eye-witnesses were coming back from Russia and speaking of the remarkable changes there. I heard John Reed speak at the Dudley Street Opera House in Boston. He set things all clear in my mind. Everything that I had been weighing and pondering over fitted together now.”

Three years later, she joined the Communist party of the USA, which was founded by Reed. In 1927, she visited the USSR for the first time and decided to stay there forever.

Painter-agitator

Mary Reed’s “sympathy for the working class“ arose when she was a child. Her mother had supported the suffragettes in her youth, but married a conservative man, Willard Reed, a Harvard graduate and a devout Protestant who worked as a school teacher and strongly disapproved of the women’s rights movement.

Mary Reed shaped her values by watching the world around. One of her friends worked in a factory and died because of strenuous working conditions before the age of 16. When she was a teenager, Reed and her family lived in Europe—and saw firsthand how the continent was being torn apart by World War I. “The horrors of war had come to me too vividly in Europe at the age of seventeen for me to accept anything which involved a repetition of them.,” she recalled in her autobiography.

When she returned home and enrolled in college, Reed started learning Russian, not yet because of the revolution, but because of the literature: she had loved Tolstoy and Chekhov in high school and now wanted to read Anna Karenina in the language it was written in. When the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia, they quickly became admired by politically active students—there were many of them in Boston at the time, just like today. Reed attended meetings of political groups where the exploitative nature of American capitalism was the main topic of discussion. At one of these gatherings, in 1918, she met a Bolshevik, Petr Antonyuk (at one point he worked for the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, but it is unclear whether he joined it before or after he met Mary.)

In the manuscript of her autobiography, Reed refers to Antonyuk as “Ivan“; it remains mostly unclear at what point she learnt that she was communicating not with a “political refugee from Czarist Russia“ (this is how ‘Ivan’ had been described in the manuscript), but with a Bolshevik agitator. Anyway, according to Reed herself and her acquaintances, Antonyuk made a strong impression on her. She liked the fact that, unlike the American socialist intellectuals she knew, who only ranted about the needs of the working class, the Russian worked as a painter and interacted with the workers as an equal.

Antonyuk strongly influenced Reed’s views: he shared the writings of Marx and Lenin with her, as well as argued for an alternative view of the events unfolding in Russia. The American press portrayed Bolshevism as a threat to civilization and democracy, and called the revolution the result of the actions of an “unruly mob“ incited by criminals. Antonyuk was presumably telling his American acquaintance that what the communists really wanted was to liberate an oppressed people and that revolutionary violence was the only way to bring about such a radical change: Reed recalled that despite all his fervor, the Bolshevik never managed to convince her that violence was justified.

After clashes with the police at various protests, she officially joined the socialist movement. In 1922, Reed received a Communist Party USA membership card. “For me it was not a matter of formality,” she wrote many years later. “It meant signing up my life [for the party], pledging myself to be bound by its discipline, to serve it above everything else.”

By the time Reed received her party membership card, she was already a married woman (her first husband is solely known to have been an employee of an export firm); in 1923 she gave birth to a boy whom she named John, reportedly after her famous namesake. However, Reed did not intend to be an ordinary American housewife: her knowledge of Russian enabled her to become a sought-after translator among the leftist press, such as The Nation magazine.

Occasionally Reed wrote original articles: about the class struggle around the world, or about the political system in Puerto Rico. But it was Russia—or rather, now the Soviet Union—that attracted her the most. “I had perhaps no greater desire than to have at least a glimpse of all that the Russian Bolsheviks had accomplished in the war-torn country,” she said decades later in an interview published in the Sovetskaya Rossiya newspaper, “to see these people’s faces, to know what is on their minds.”

The country ruled by hammer and sickle

In July 1927, Mary Reed’s dream came true: she arrived in the USSR as a journalist for several American publications at once (the aforementioned The Nation published a major article on the Soviet health care system penned by her). The 30-year-old American did not return to her homeland: she liked it in Moscow, and it quickly became clear that her skills and experience as a translator qualified her to work in the USSR as well.

Both Reed’s homeland and her new country of residence were undergoing immense change at the time. Six months after Reed’s arrival, the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks (later known as the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) took place, which hailed the defeat of the Trotskyists; a year later, Stalin removed Bukharin and other “right-wing sympathizers“ from positions of power, which effectively transformed himself into the sole authoritarian ruler of the USSR. The relatively liberal New Economic Policy (NEP), pursued between 1921 and 1928, was abandoned; forced collectivization and forced industrialization took its place.

At the same time, the United States was experiencing the worst economic crisis in its history: during the Great Depression, 13 million people lost their jobs. For the first time in history, the flow of migrants went not from Russia to the United States, but in the opposite direction: the Soviet Union attracted Americans with its relative abundance of jobs, as well as free education and healthcare. For example, the Amtorg joint stock company from New York, which promoted Soviet-American trade, received more than 100,000 applications for immigration to the USSR.

“...Engineers, factory workers, teachers, artists, doctors, even farmers, all mixed together on the passenger ships,” writes journalist Tim Tzouliadis in his book The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin's Russia. “Within their ranks were American communists, trade unionists and assorted radicals of the John Reed school, but most were ordinary citizens not overly concerned by politics.” Americans were employed in factories all over the USSR, schools were opened for their children to attend, they even brought their national sport with them: at one time there was a dedicated baseball team at the GAZ automobile plant.

Mary Reed worked as a translator for the Comintern executive committee: the duty of this organization was to coordinate the activities of communist parties around the world, theoretically—to eventually stage a world revolution, in reality—so that the Bolsheviks could expand their sphere of influence. Mary Reed worked on her translations from home: she was considered to have a disability of the second degree and was allowed to not attend the office (Holod was unable to exactly identify Reed’s illness, but among disabilities of that degree are partial paralysis, significant loss of vision, and psychological diseases).

In her spare time, she engaged in literary work: she wrote short stories and poetry. Her poetry was later translated into Russian by the Soviet poet Yefim Shklovsky. In Russian Reed’s poems look like boilerplate political poetry, but how this corresponds to the original is unknown: the only original poetic text by Reed which Holod managed to find was written in free verse. It is a dedication to Alik Rivin, a Leningrad tramp poet who lived off acquaintances, begged, caught and sold cats for experiments, and died during the blockade under unknown circumstances; Reed mentions in a letter that the poem was about love. In Rivin’s own first collection of poems, which was published in 2022, Mary Reed is mentioned in the ’drafts’ section: “To my grave / Mary Reed will not come / Only my unkind father / Will bury me.”

In 1929 Reed dedicated a poem to her son:

Here’s its English version as translated back from Russian by Holod:

And you will ask me: “Why Is my father in America, while you’re in Russia and you don’t want to live with us?“ And I shall answer: <...> There exist two classes, Your father lives in one, And mother—in another. <...> But one day you will understand, that there is a struggle which divides the world, that there’s a country where the dollar rules all, and there is a country of the Hammer and Sickle rule.

Little John got to see the country where the Hammer and Sickle ruled in 1931, when his grandmother brought him to visit his mother. At least that was what his father had been promised, however, since then John never left the USSR.

In November 1932, a reception for a communist delegation from England was held at the hotel Luxe in Moscow, where Mary Reed met 25-year-old Len Wincott, a former sailor in the Royal Navy who had organized a strike when the British government lowered sailors’ wages. “It was love at first sight,” Reed recalled. Wincott felt likewise.

A year later they got married: at first Wincott used to visit Reed in the USSR, they exchanged letters, and once she managed to come see him in England. In 1934, Wincott moved to the USSR. Just a year later the spouses separated, but stayed in touch. A few years later this short relationship with an Englishman would play a malevolent role in Reed’s fate.

By the time she parted ways with Wincott, Reed and her son were already living in Leningrad and had both become Soviet citizens, but the political atmosphere in the Soviet Union had changed drastically once again. Stalin used the assassination of Sergei Kirov, leader of the Leningrad Party Committee, as an excuse to introduce mass repression. Newspapers printed seemingly endless articles on each new arrest of a high-ranking official who was accused of collaborating with foreign intelligence. Foreigners living in the USSR began to arouse suspicion.

Reed no longer worked for the Comintern, whose members were also regularly repressed. While in Leningrad she worked as an English tutor, an educator for the kids of a doctor from a local hospital, and in 1937 she became a reviewer of American literature in the local department of the Gosizdat state publishing house.

Meanwhile, her son John attended a regular Soviet school. Some of Reed’s friends got arrested, but she remained personally unaffected by the wave of repression. Then the war began.

A starving person

When Nazi Germany attacked the USSR, John Reed had just turned 18. He felt like a true Soviet citizen: after finishing school, he got a job as an electric welder at the Zhdanov Plant, where he not only worked “with unbelievable passion,” but also engaged in political agitation. It was crucial to his mother to create a normal life for her son: “Being able to eat something, rest in a clean bed, feel relaxed—all of this was necessary for a boy who worked sometimes two or three shifts in a row.”

On September 8, 1941, the Siege of Leningrad began. Famine soon struck the Reed family. Mary’s daily ration consisted of 125 grams of bread. “I was able to grip my arm above the elbow between my index finger and my thumb,”Reed wrote in her diary on November 14, 1941. “Two days ago the fingers wouldn’t touch.” As public transit ceased operation, John had to walk across the city daily to get to the factory—despite the bitter cold and overall weakness. His mother tried to persuade him to take a sick day, but he insisted that he had to publish the new issue of his bulletin-board newspaper. Eventually John succumbed to pneumonia and died at home on December 19, 1941, while staring into his mother’s eyes.

The American’s labor and work experience were unwanted. “We have no need for a specialist in your field,” the head of the military department of the district party committee told her. “I devoted my life to these people and others like them,” Reed later said of her Leningrad neighbors, "but they are so frightened that when fear overtakes them, they begin to see me as a spy.” Old friends like the writer Olga Bergholtz turned their backs on her. In her book Notes From the Blockade, Lydia Ginzburg characterized Reed based on their casual conversations as follows: “What can she write about current affairs? A starving person, who was in a dystrophic state for a whole year. What does she know? All the while everyone says that she is worthless.”

At the height of the siege, Reed began working first for the Radio Committee and then for the Sovinformbureau. Gradually she became disillusioned with the party apparatus, though not with the party itself and its ideals. At the end of 1944, in her diary, she wrote that the whole official party apparatus of Leningrad “stinks”, and there are no real communists among them. And in June 1945, after the defeat of Nazi Germany, the American wrote a letter to Stalin in which—like many Soviet writers before and after her—she complained that no one would publish her work. “With my literary work I can play an important role in strengthening the ties between our peoples [Soviet and American],” Reed argued. “Yet my writings are not even acknowledged here because supposedly ’there is no one to translate them, no one to print them, and they are not written in the conventional manner.’“ Reed asked the leader to personally decide “whether the Soviet Union, for which I have sacrificed everything in my life, really needs me.”

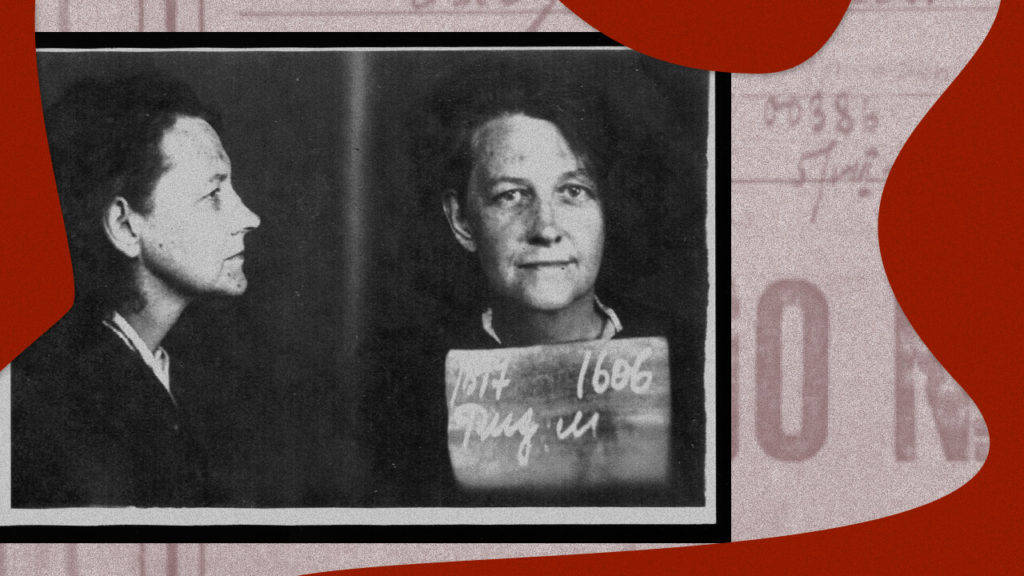

Two weeks later Mary Reed was arrested and charged with espionage.

Anti-Soviet slanderous insinuations

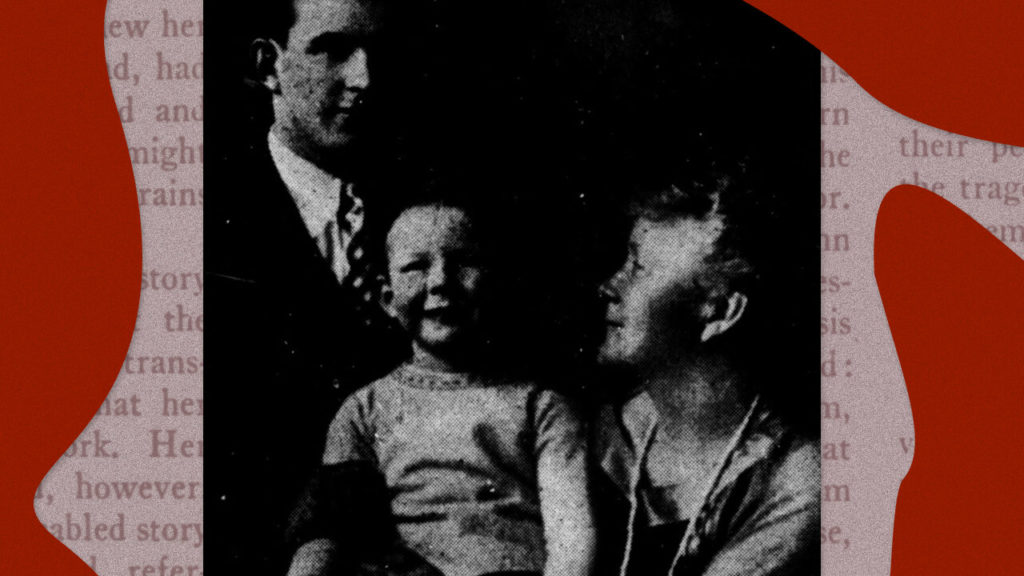

In October 1946, Life magazine published an article about three elderly women who acquired the US Communist Party newspaper, Daily Worker (they bought it so that the paper, which received money from the USSR, would not have to register under FARA). One of these women was Ferdinanda Reed, Mary’s mother. By this time Nancy, Mary’s younger sister, had already lost her job with the Labor Department in New York City because of her Communist connections, and her younger brother had been killed in the war.

Among other things the article states, “Mary, who was a charter member of the US Communist party, has been living in Russia since 1931 and has not been heard from since her health broke down after the siege of Leningrad.” By that point, Ferdinanda had been waiting for a visa for two years.

While relatives from across the pond were trying to contact Mary Reed, she was under arrest. Her criminal case was under investigation. From July to November 1945 she was interrogated at least once a week. According to records, these sessions went along these lines:

— The investigation is in possession of material proof that you have engaged in espionage against the USSR. Once again, the investigation invites you to cease your secrecy and give truthful testimony about your intelligence activities against the USSR, which you were engaged in.

— I will say it again: I have never engaged in any anti-Soviet espionage.

— You continue to blatantly lie.

The chekists, Soviet secret police operatives, were especially interested in Reed’s relationship with Len Wincott: he was arrested as a suspect in the same criminal case three months before Reed. The third offender was Tatyana Gnedich, a translator. According to the investigation, Gnedich was part of an anti-Soviet group within the Leningrad branch of the Union of Writers which aimed at overthrowing the communist regime in the USSR and was also gathering intelligence for the English spy, Wincott.

Reed was initially accused of aiding her ex-husband in recruiting Soviet citizens, but then the charge was changed to anti-Soviet propaganda: she allegedly traveled to Britain to give Wincott denigrating information about life in the Soviet Union, spread her “anti-Soviet slanderous insinuations“ with acquaintances and recorded all of it in her diary, which she wanted to publish abroad to belie the Soviet State.

This accusation she admitted—at least judging from the interrogation protocols; but since these documents were created under the investigation’s complete supervision, one ought to be skeptical towards the information contained in them. Reed told the investigators that she wrote in her diary that the party officials in Leningrad were “rotten,” that the USSR lacked democratic values similar to those in America, that the party had set itself apart from the people. “I falsely claimed that NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs—ed.Holod) officers, instead of catching saboteurs and robbers, were harassing all the foreign communists in Leningrad and making their lives hard,” Reed said, according to the investigation documents.

On February 26, 1946, Mary Reed was sentenced to 5 years in prison and two years of disenfranchisement by the NKVD Military Tribunal. Len Wincott served ten years in the Mineralny Camp Directorate, part of Gulag, in the Komi ASSR. He was released in 1955. After he wrote a letter to Nikita Khrushchev, Wincott was rehabilitated (his reputation was restored as he was recognised to have been prosecuted without due basis). He moved to Moscow, got an apartment and married a Russian woman. He had given up on his communist delusions long ago. Tatiana Gnedich was also sentenced to 10 years in a labor camp and was rehabilitated in 1956; she lived for another 20 years more and was reinstated in the Writers’ Union, where she was a successful translator.

Reed served her sentence in the Yaroslavl region. Little is known of the years she spent in the camp. Evidently she never saw Wincott again. He did not even mention her in his memoirs, and there is no mention of Reed in other people’s accounts of Wincott’s life.

The heart of Tuma

In 1950, Reed came to the worker’s settlement of Tuma in the Ryazan region: she had been released from the camp and sent there for resettlement. She brought only a small suitcase and a certificate of release from the labor camp. “The locals were wary of her,” recalls Nina Filchenkova (Zakharova), a resident of Tuma, who sometimes helped out the American back when she was a schoolgirl. “These days she would be considered a homeless person: a she wore wool socks and galoshes, a sackcloth skirt, a vest-type jacket, and a headscarf.

Tuma is a small urban-type settlement, where the main attractions are the local church and a forest park; its current population is about 5,500 people. Trains get off Tumskaya station only twice a day—to Vladimir. Most residents here know each other—and know about Mary Reed: her poems are read at township events, schoolchildren write papers about her, and regional newspapers mention her as a well-known resident of Tuma.

At first, Reed lived in the hallway of an apartment building near the sawmill, where she was given a few square meters divided from the rest of the space with wooden planks. “Mary had no stove or heating, only a kerosene lamp. I used to bring her water and in the winter she would freeze, it was so cold in that room,” says Rimma Kovrovskaya, 84, who met Reed on a walk in the park in August 1952.

The 14-year-old girl and the 55-year-old American woman became friends and started meeting regularly. “She had to have someone by her side,” Kovrovskaya explains. “I used to come visit and take care of her. It’s only now that there are lots of volunteers, but back then we didn’t have that.” Kovrovskaya says she would see Reed daily. Together they went to the park and the riverside; the American taught her English.

According to Kovrovskaya, in her first few years in Tuma, Reed only had a part-time job cleaning sawdust at the sawmill for 10 rubles a month, and later began receiving a small pension. Kovrovskaya’s aunt used to patch up and mend the writer’s clothes. A few fellow villagers would occasionally visit her.

Every year Mary, accompanied by Kovrovskaya, would attend the November 7th demonstrations (celebrating the Communist Revolution anniversary). “Even if she was disappointed in the party, she never showed it, never complained,” Kovrovskaya says. “She believed in the party all her life.”

Reed regularly wrote letters to high-ranking party officials such as Stalin, Molotov, and Beria, in which she told them that she had left her homeland to help build socialism, recalled her experience in the Comintern and Gosizdat, and declared her loyalty to the Communist Party. “And what was her reward? Living in these conditions,” Kovrovskaya continues. ”I would come back from college to visit her and plant potatoes with her under her window, I would wash her and trim her hair, and I would take all her letters and notes and buy her medicine.”

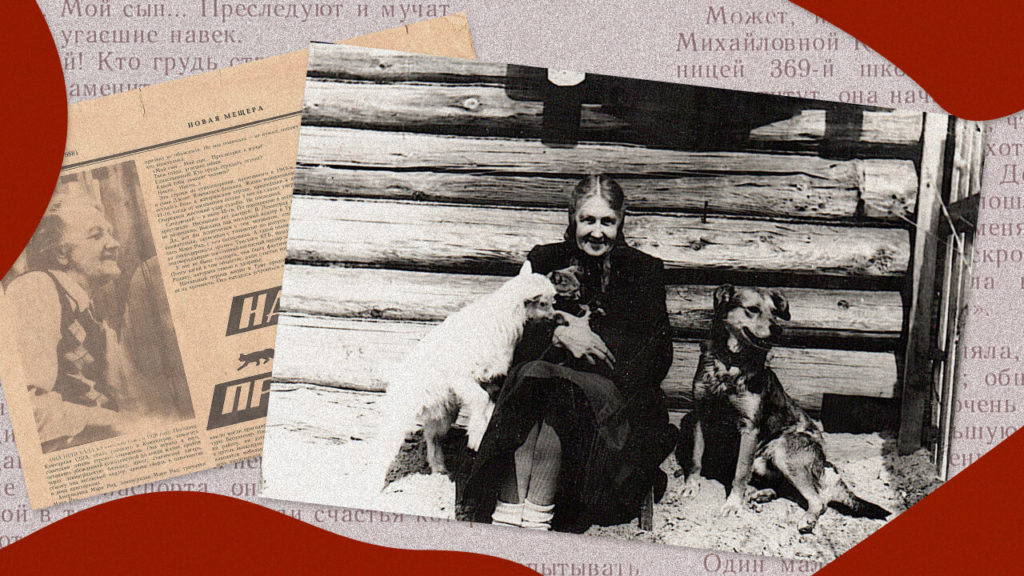

сторонились: с ней начали общаться соседи, американку стали навещать тимуровцы. In 1956, at the age of 59, Reed was rehabilitated and reinstated in the party. Her pension tripled; the local government gave her half a house and built a barn, and a furniture factory gave her furniture. Reed had a goat, raised chickens, and simultaneously translated poetry into English, composed her own original works, and wrote an autobiography. The people of Tuma no longer shunned her: Neighbors began to socialize with her, the American began to be visited by timurovtsy (a youth charitable organization).

In the early 1960s, Rimma Kovrovskaya, who had begun working as a schoolteacher in her home village by then, suggested that the children in her class ought to start helping Reed out. That’s how fifth-grader Nina Zakharova met the American. “Everyone agreed [to the teacher’s offer]. Everyone was curious about her—she was an American,” she recalls. Reed herself said in letters that the students tidied the yard, cleaned the floor of the house, and chopped firewood for her.

Upon her rehabilitation, the district newspaper began publishing articles about Mary Reed. Thus, in 1966, the Novaya Meshchera newspaper published her poems translated by Efim Shklovsky. One of them is dedicated to Tuma and ends with the following lines:

Here it is as translated back to English by Holod:

And no matter The hardship of my age I smile Towards the people. I am near them I’m not alone And ringing joy Knocks on my windows And the tighter my hands The brighter my thoughts And I was lucky To know your heart, Tuma The Russian land On any glade Accept the heart Of an American.

In the mid-1960s Mary Reed was visited by her sister Nancy and her husband. Filchenkova remembered well the differences in the sisters’ appearances: “We didn’t know what hair dye was back then, and Nancy had dyed, permed hair and looked quite young. Even though Mary was only a few years older, her hair was gray and looked like oakum.” Her sister offered Reed to return to America, but she refused.

“Why do you think she didn’t leave?” Kovrovskaya asks. ”She left her home in America in 1927, she was a citizen of the USSR, she joined the Communist Party of our country. And how would she be able to travel since she was so sick and old? She never even dreamed of it.”

The last wish

In 1967, before the very end of the Khrushchev Thaw, Mary Reed broke her hip and was hospitalized in Ryazan. According to Rimma Kovrovskaya, this is how the regional center learned that an American woman lived in one of the villages of the Ryazan region. After that, the state press began to pay more attention to her and publish her poems. She admitted: “I’m old now, I had a broken hip, and moving is still difficult for me. But I am very happy that the meaning of my life has begun to reach the people.”

Journalists and photographers began coming to Tuma. In the articles published in those years the authors glossed over many details of Reed’s biography such as criminal prosecution, resettlement, and difficult living conditions. For example, Shklovsky, who translated her poems, wrote the following in one of his articles: “The war, the Siege of Leningrad, the loss of her son undermined Mary’s health. She settled in the quiet village of Tuma, surrounded by the picturesque nature of the Meschera.”

Three years later Reed was offered to move from Tuma to one of the nursing homes in the Ryazan region, and she chose the one in the town of Mikhailov, where Rimma Kovrovskaya lived at the time.

“I visited her almost every day and stayed around with her all day, even though I had my work at school and two children to take care of at the time,”Kovrovskaya recalls. ”Mary lived happily, by the way, in a single room, with all the amenities, she was well cared for; she was even allowed to keep her dog.” In an interview with a local newspaper, Reed said she had never had such excellent working conditions and that finally nothing could distract her now.

She was cheerful, full of optimism and ardor. "She expressed her readiness to work for the good of her adopted homeland, her beloved Soviet country for the rest of her life," reads a newspaper clipping from 1971, which Kovrovskaya preserves to this day. During these years Reed wrote many letters to America, both to old friends and new like-minded people. Through acquaintances she managed to send a letter to the New York prison where Angela Davis was held, an African-American activist who had been arrested on fabricated murder charges and whose story the Soviet media had covered extensively. Reed sent Davis her translation of Pushkin’s poem which was written in support of the Decembrists, "In far Siberia’s deepest soil...," as well as a letter from Ryazan’s schoolchildren in support of the political prisoner. After a while the activist replied:

“My dear comrade and sister! Your poem was beautiful and inspiring; it articulated so well the solidarity and love we must all learn to feel if we are to ultimately be victorious over the enemies of a free humanity

Much love,

Angela Y. David.”

Reed received this letter while already in a nursing home for the veterans of the revolution, political prisoners, and diligent workers in Peredelkino, where she moved with the help of the aforementioned Efim Shklovsky; not only did he translate Reed's poems, but also became friends with the poetess. According to Kovrovskaya, the American dreamed that in Peredelkino, which is very close to Moscow, she would be visited by her old friends more frequently. But no one ever came and a few months later Reed fell ill with severe pneumonia, the disease that brought her son to his demise. She died in March 1972, aged 74.

One of Reed’s poems is titled The Last Wish:

Here it is as translated back into English by Holod:

When at my last hour The dear party wished to know of my last wish I would answer, “I am a part of your life, And, like light fading away, I fear not the night. No regret, since in every moment Of your struggle I have given you all my heart. And the spring of my soul never did fade. And I was never weary walking this road with you. If I should live no more There's one thing I wish for at the bottom of my grave, That my death, as my life, may serve An example of faithfulness, steadfastness and strength.”

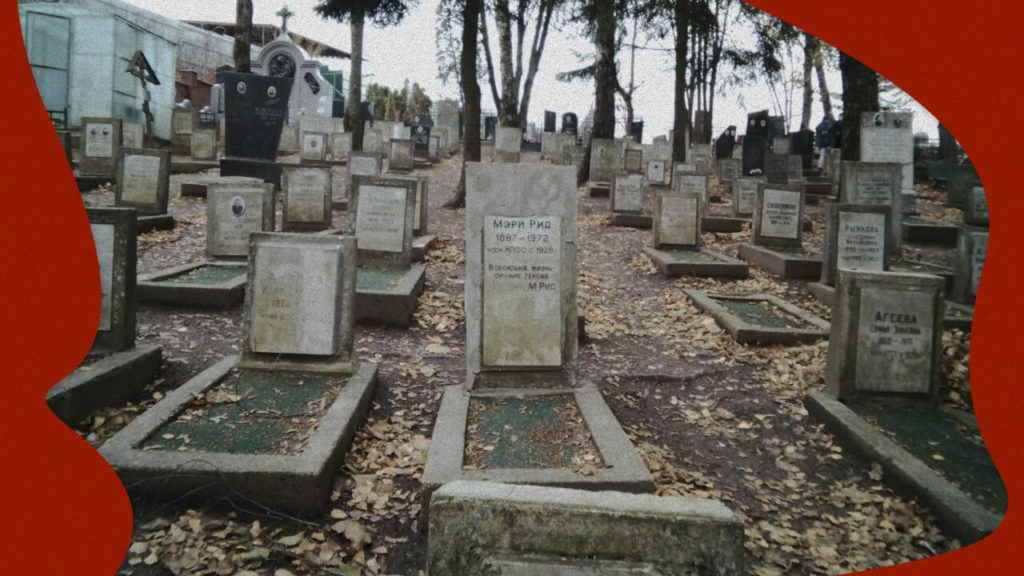

Mary Reed is buried in the party members' plot in the Peredelkino cemetery. Her tombstone stands out from the uniform gray memorials. The engraving on the tall granite stone reads: “An All-Powerful Life is the Weapon of Heroes.”

The memory of an American woman who believed in communism and the Party all her life is kept alive today by only a handful of people. Handwritten notes on Stalin's and Lenin's writings, several articles and photographs are in the museum section of Tuma School No. 46. Letters from family and friends, clippings of newspaper articles about Reed and part of her handwritten autobiography are carefully preserved by Rimma Kovrovskaya. Several more newspaper clippings have been preserved by Nina Filchenkova, 71, who as a schoolchild would help out the American. “I have a family archive, a folder about yoga classes, a folder about cooking,” she says. “I have Mary in my ‘anomalies’ folder along with extraterrestrials.”