Russian invasion of Ukraine is ruining lives, cities, families. It has also destroyed common cultural space centered on Moscow which, regardless of any geopolitical conflict, existed up until February 24th, 2022. Holod’s editor and music journalist Alexander Gorbachev explored this space as part of several projects over the recent years. Now he takes a look at this new reality, specifically the pop music, and tries to identify the outlines of the emerging cultural landscape.

What a sorrowful thing this, that today you’ll conceivably play a promotional requiem and, without hackle or heart in the venture, mention log roads made up of men’s flesh, half a vodka for pay, laid so lavishly over your watery bog of a culture.

Viktor Krivulin. «Daughter of Kolyma»

(translated by Thomas J. Kitson)

1

I thought I was writing a panegyric, but it turned out to be an epitaph.

About a year ago, Don’t Be Shy was published, an oral history of 169 pop hits that defined the musical code of mass culture in post-Soviet Russia... I wrote and edited the book. 2 million characters, 1.7 kg—his seemed like a rather appropriate size to celebrate how over the past quarter century the word popsa (in any case, what is understood by it) went from an insult to a compliment, while pop music became perhaps the most lively and interesting sphere of Russian music.

The dates 1991-2021 on the cover don’t imply any specific end (in fact, we originally aimed to publish the book in 2020). The book wraps up with an enthusiastic monologue from Slava Marlow, who produces Morgenstern, the biggest Russian pop-rap hitmaker of recent years: “I have a feeling that in the next 10 years money will come to Russian music, and then even the creators who don’t have many listeners will live better. And there are just so many new names now in music, in rap! Everything is great. It's really interesting to see what will happen next.” In a sense, the book's storyline followed a paradigmatic quote from an old Russian state security chief: “The past of Russia was amazing, its present is more than magnificent, as for its future, it is higher than anything that the boldest imagination can imagine.”

Essentially, that's how it turned out. Even the wildest imagination couldn’t imagine that on February 24th the future would simply be cancelled. Now the dates 1991-2021 clearly look like an inscription on a tombstone. But whose grave is it?

To provide a clear answer to this question, we should go back ten years. The first part of the future Don’t Be Shy was published in December 2011 in Afisha magazine—at that time the editors had just begun to master the genre of oral history, applying it to the archeology of modern Russian culture: media, advertising, cinema, the internet and of course pop music. On the cover of that issue was written: “99 Russian hits.” The word “Russian” is important here: some of the songs were written and performed by Ukrainians, Belarusians, Kyrgyz and other foreigners; now this wording looks like an obvious example of imperial chauvinism, albeit unconscious. In 2011, it didn’t seem like that. In any case, such questions didn’t occur to the people in the editorial office who made and released the cover, nor to the heroes of the piece, nor, as far as I remember, to the readers.

After 2014, language changed along with reality. When we made Don't Be Shy, it was obvious that the title of the book referenced a song by Ukrainian Ivan Dorn, and the word russkiy would be completely inappropriate. As in fact would the word rossiyskiy—and it wasn’t only about the citizenship of who made the hits, but also the space across which the hits spread: it would be strange to confine within Russia’s borders songs that are sung with equal enthusiasm in Omsk, Riga, Kyiv and Almaty.

Thus, the subtitle was formulated like this: “The history of post-Soviet pop music in 169 songs.” That said, this formulation required additional commentary. Here is what I wrote in the preface to the book: “We decided that ‘post-Soviet’ is the most correct and understandable description for the cultural space in question. Also because pop music is one of the few things that still unites our countries, despite everything else.”

I must admit that this thesis—about culture bringing us together despite everything—was really very dear to me, and in the years before the war I actively forced it into my projects. Don't Be Shy was produced and published by the Institute of Music Initiatives. Another joint project of ours was a series of collections of semiacademic articles under the umbrella title Novaya Kritika—while soliciting entries, we emphasized that we were interested in “new points of view on post-Soviet pop music.” In collaboration with the Moscow studio Stereotactic, we made a documentary series about music called Potok, whose heroes were producer Yuri Bardash, a native of Lugansk Region who lived in Kyiv at the time, and Muscovite Azeris, who created the Zhara Music pop label.

In fact, that's whose grave it is.

This is a completely obvious conclusion, and I’m not the first to formulate it, but it still must be stated. The next question is: well, what does it mean? Is it actually a big problem? Russia is the biggest and richest of the former Soviet republics, a huge cultural market. Is the damage serious? Doesn't Russia have enough of its own cultural resources?

No.

2

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia declared itself the successor to the empire. This brought certain obligations, but also certain advantages, including in a cultural sense. Even with all the rhetoric about the equality of the newly independent states, Moscow of course retained the symbolic status of the metropolis. This directly affected the new Russian pop music: on the one hand, it parted ways with the Soviet tradition stylistically and aesthetically; on the other, at the personnel level it completely inherited the Soviet project, one of the tasks of which was to incorporate various peoples into a single collective Russian-speaking nation.

The people who made Russian pop music in the 1990s were often not from Russia—as it existed within its new borders. Fashionista Bogdan Titomir, who brought Hi-NRG sound to the Russian pop scene, was born in Odessa. Arkady Ukupnik, the producer of Titomir’s Car-Man band and later one of the most successful Russian pop composers, is from Khmelnytsky Region. Singers Natasha Koroleva and Tatyana Ovsienko are from Kyiv (Ovsienko's mother and sister still live there). Zhenya Belousov, a favorite with ladies who died young, hailed from Kharkiv. Lolita Milyavskaya, of a comic pop duo Academia, is from Transcarpathia, Anzhelika Varum from Lviv and Alexander Serov from Mykolaiv Region. Bari Alibasov, who produced the boy band Na-Na, lived, studied and worked in Kazakhstan until the end of the 1980s; singers Linda and Murat Nasyrov were also born there. Composer Igor Kornelyuk is Belarusian. Singer Vlad Stashevsky was born in Tiraspol and grew up in Crimea. Larisa Dolina was born in Baku and started her career in the ensemble We Are Odessans. This list can be continued—I haven’t even mentioned the Meladze brothers or Philipp Kirkorov.

Russian pop music also inherited the practice of political loyalty to the state, which was assumed as if automatically. In Soviet times, the music industry was patronized and financed by the state; apparatchiks and ideologists controlled, if not the music, then certainly the message behind Song of the Year, the biggest pop contest on television. Amid the wild capitalism of the early 1990s, popsa, which until then had effectively survived thanks to budget flows and was now forced to earn money on its own, suddenly became the main commercial music genre. In those years, there were certain ideological rumblings.

However, it quickly became clear that music with pure entertainment content brought profits much more reliably. Meanwhile, everything gradually returned to normal: the state began to reclaim financial and media resources, and for artists who still remembered the Soviet years, loyalty seemed quite natural. As it was for the audience: it is symptomatic that disputes over whether rock bands should have toured in support of Boris Yeltsin’s 1996 presidential bid are still ongoing, while the pop tour called Yeltsin is Our President organized by producer Igor Krutoy has never been called into question.

With the onset of the Putin era, the alliance was firmly cemented. The key media were divided up into spheres of influence among the main industry players—first and foremost, among producers and production houses at least ready to cooperate with and at most to fully support the state (see the president's relationship with producer Igor Matvienko and his band Lyube). The main source of income for pop artists was corporate events—and since the state soon took over all big business, the music industry now depended on a small group of regular customers instead of a wide audience to which you could sell hits: why waste money on tours around the country if you can get a fee for one New Year's show equal to that of ten concerts? This, in my view, partly explains the visible stagnation in Russian pop music in the mid-late 2000s—when the conveyor at Star Factory, a Russian analog of The X Factor reality show, stamped out songs and artists based on old criteria and basically in the absence of real competition, which a few years earlier had stimulated the same producer-tycoons to come up with something new.

All that, still, didn’t change the fact that Moscow remained the main cultural market for neighboring countries. However, something was different.

The heroes of the following generation—who had managed to live in new countries, who had gradually acquired their own style, sound and image—behaved somewhat differently. Belarusians Byanka and Seryoga translated American R'n'B into Russian (Byanka’s most successful album was literally called Russian Folk R'n'B), but also found their own intonation, which then would resonate in the music of LSP and Max Korzh. Ukrainian Verka Serduchka became a star of Moscow corporate events largely thanks to his entertaining and inventive exploitation of stereotypes about Ukrainians and Ukrainian culture. BoomBox sang simultaneously in Russian and Ukrainian, which didn’t stop them from making it into the heavy rotation on Russian radio stations.

As Putin began to formulate his foreign policy of confronting an imaginary West and denying Ukrainian statehood, there were of course warning signs. Three months after he delivered his so-called Munich speech (2007), Russian state media went hysterical over the Eurovision song of the same Serduchka, in which they thought they heard “Russia, goodbye” (after that Serduchka was said to be banned in Russia but still continued to perform). However, at the time it was still perceived as an obvious pathology: Eurovision is a political contest, it has its own atmosphere, yet it shouldn’t hinder multinational pop scene.

And then the annexation of Crimea and the “Russian Spring” happened, and everything should’ve changed. But it didn’t.

3

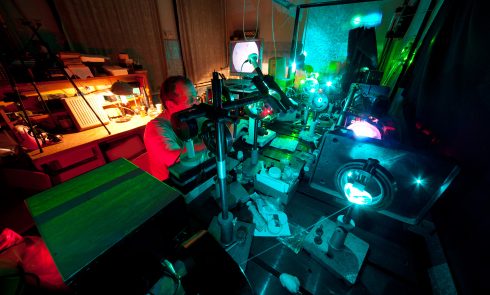

In May 2014, I went to interview Maxim Fadeev, one of the top Russian pop producers, in his studio in the basement of the skyscraper at Sokol called Triumph Palace. With great enthusiasm the producer showed me the English-language tracks of Olga Seryabkina—featuring hip trap beats, laying out his plans to expand into the Western market; however, at the same time he argued how Vladimir Putin had united the nation and “tightly riveted a feeling of patriotism in the souls of young people.” Back then, it was still possible not to sense the contradiction. Fadeev was sure that it was on the wave of popular enthusiasm about Crimea that a big new pop star would emerge.

A big star—and not just one—did indeed emerge, but it was rather in spite of Crimea. If before 2014 the post-Soviet Russian industry had existed parallel to politics, then after Crimea it began to live perpendicularly.

Who moved pop music forward in Russia in the last eight years? The Kazakh Skryptonite, who has consistently defended his non-Russian identity and convinced the last doubters that hip-hop in Russian could be musically original, creating an intonation and manner that the writers of commercial hits began to adopt. Azeri producers and artists from the aforementioned Zhara Music honed and capitalized on so-called hookah rap, a genre combining glam club sounds with a tough southern vibe that pumps out radio hits. Belarusian Max Korzh, packaging hip-hop bravado, broishness and the electronic aggression, began to fill stadiums, creating a whole fan movement and a legion of imitators.

But the main foreigners in Russia after 2014 were still Ukrainians. Ivan Dorn made pop music fashionable, cool and interesting again. Svetlana Loboda and Dmytro Monatyk returned chic, brilliance, entertainment and provocation to television screens. Producer Oleksiy Potapenko (Potap and Nastya; Vremya i Steklo) adapted Soviet pop melodies and aesthetics to new dance grooves.

The singer Luna managed to use the unending nostalgia for the sound of the 1990s to create a new style (the Russian Elena Temnikova did the same—this is how house pop came about, which has dominated radio waves in recent years). The band Griby definitively proved that rap can be pop music for all ages and people. Poshlaya Molly resurrected rock as rave and created a sound template for dozens of bands that exploit teenage sexual frustration.

In the 2010s, Ukrainian dominance turned into the status quo. Both Dorn and the rest were constantly asked in interviews: how is it that Ukrainian pop music is so much better than Russian? And they would patiently explain that the media landscape in Ukraine was arranged differently: fewer controls, more competition, hence the willingness to take risks and invest in new things.

None of them concealed where they were from. Ivan Dorn managed to perform at the official New Wave pop contest in a T-shirt with a Ukrainian trident a few months after the annexation of Crimea. Having represented Ukraine at Eurovision and having done a lot of charitable and media projects in her homeland, Loboda lived between Kyiv, Moscow and Los Angeles. Griby’s first bout of success was directly connected with the mass entertainer Kyivstoner, who infused their disco gop hop with stories in pidgin language—regarding the super hit Tayet led (The Ice is Melting) the producer Yuri Bardash even said that it was about relations between Russia and Ukraine.

Overall, while Russian television was dehumanizing Ukrainians, Ukrainians were humanizing the Russian stage.

This paradoxical situation can have two interpretations. The first—which I preach, on which Don't Be Shy is ethically founded—sounds like this: pop music supported peace and united people in spite of politicians, and tried to bring humanism into an inhumane media space. The second interpretation could go like this: it was all a screen, even if it was built unconsciously by many people. The songs and dances covered up imperial ambitions and preparations for war, helped everyone pretend that everything was OK when everything was not. The musicians, flattered by the audience and money, unwittingly worked to create the colonial lens through which Russians perceived Ukrainian artists as their own. Had these ties been severed sooner, the threat would have been more visible.

It seems that along this line Ukrainian journalist, promoter and publisher Sasha Varenitsa directed his criticism of Don't Be Shy. His main thesis was that no matter how much Russia hides behind the term “post-Soviet,” the book’s authors look at Ukraine and write about Russia—they should admit it and honestly delete what isn’t theirs from their history: from Natasha Koroleva and Makiivka native Mikhey to Time and Glass and Estradarada. The proposal didn’t make sense to me in August 2021 and still doesn’t. The undertaking would be senseless: the complexity and interestingness of the Russian stage from 1991 to 2022 largely owed to the fact that it was impossible to artificially remove Ukrainians, Belarusians, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Azeris, Georgians, Armenians, Latvians and so on. Moreover, though there may be different viewpoints on the fact that they inhabited a single cultural space, the space did empirically exist.

But it doesn’t anymore.

4

What now? Let’s try to speak in the present tense, not the future. At first, reflections about the war had a strange temporality: what was happening here and now felt too real, too unbearable, so the main conversations revolved around the past (how the war became possible) and the future (how to make everything right later). Seven months of war without much prospect of a resolution—especially if we talk about Russia and its domestic politics—force us to return to the current moment.

If it hasn’t collapsed, then the Russian music industry has significantly shrunk. Spotify left the country completely. Apple Music stopped updating Russian showcases and playlists, meaning it has lost its relevance as a promotional tool. Music companies are also on the way out—on September 8th, Sony Music, one of the global majors, announced that it was entirely leaving the Russian market. Michael Jackson and many other classics will now be much more difficult to listen to legally in Russia.

In addition, fewer people are ready to perform: market participants surveyed by Kommersant say that “up to 30% of Russian artists” have left or stopped giving concerts.

It's clear who these “Russian artists” are—at least partially. Ukrainians are no longer involved in Russian pop music. Monatyk recorded a mini-album about the war in Ukrainian. Luna, having sat in a Kyiv bomb shelter with her children, canceled a tour across Russia and the release of her album in Russian. Oleksiy Potapenko has effectively turned his Instagram into a counter-propaganda, anti-Putin media. Vera Brezhneva is unloading humanitarian aid. Verka Serduchka is now really singing "Russia, goodbye.” All these people—as well as Svetlana Loboda, Poshlaya Molly and many, many others—are giving concerts all the time with some or all of the revenues going to support refugees and the Ukrainian army (a rare exception is Yuri Bardash). None of them will ever go back to Putin's Russia or perform at a corporate party.

The most striking and tragic story is clearly that of Ivan Dorn—written up well in The New York Times (characteristically Dorn agreed to speak with an English-language publication). Dorn really believed in people and really bet on the power of art. He created the accelerator label Masterskaya, which helped both Ukrainians and Russians find their sound and their way; he collaborated on an environmental campaign with Moscow's Garage Museum, becoming one of the few successful musicians in Russia to talk seriously about the climate crisis. His album Dorndom, which would have been his first in Russian in eight years, was set to be released on May 31st and become essentially the main music event in both Russia and Ukraine. Dorn told the Times: “My idea was this: I capture as many people as possible with my music so that they would never attack my own country. I was confident that people who came to my concerts would not fight in a war against Ukraine.” Even in the first days of the war, he desperately appealed to Russian listeners—without malice, without anger, begging to be seen and heard. His kindness was drowned out by exploding rockets.

Ukraine is the biggest, but by no means only loss for “post-Soviet” Russian pop culture. In the first days of the war, Skryptonite closed his label and media, left for his homeland in Kazakhstan and now opens his concerts with a moment of silence. Max Korzh, has canceled concerts across “our countries” (a very telling formulation), took a clear position in the very first hours after the invasion and has recorded some of the best songs about the war so far, succinctly translating the geopolitical collisions into the language of his bros: “Whoever is defending his home is in the right.” These are all leaders in their respective niches, and though Belarus is still too attached to Russia for its musicians to disassociate themselves completely, they will obviously crawl away from the toxic neighbor as soon as the opportunity presents itself. The Azeri diaspora continues to make hits in Moscow—but who can say whether that’s for good (especially taking into account such statements). In 2021, Zhara Music, led by the main producer of hookah rap Bakhtiyar Aliyev, officially became the Russian branch of the influential Western label Atlantic—since February 24th there hasn’t been any updates on the page of the “legendary global music label Atlantic Records Russia.”

In one way or another, neighboring states have perceived Moscow as the Constitutive Other for 30 years, i.e. the reference point from which they must build out. Thus, they cultivated their own cultural fields as fundamentally different from the self-proclaimed metropolis. Meanwhile, Russia proudly constructed a composite, umbrella, imperial—if you will—identity. Now, it faces the prospect of building its own separate identity if not from scratch, then from a clearly worse starting point.

How will it do that?

One potential vector is an emphasis on the popular, the folk, the ethnic. After Channel One announced that it would bring back entertainment programming, among the first shows announced was The Whole Country Sings in the Kitchen, positioned as a “nationwide drinking song competition.” As far as can be gleaned from the previews, a gray-haired Valdis Pelsh (by the way, a native of Riga), against the background of LED screens with khokhloma, invites families and performance groups in folk costumes to perform a folk repertoire for the jury, pedaling so-called traditional values. The idea is understandable but hardly viable in the real context of entertainment: after all, people dance to pop music in clubs more than daydream in hay.

A qualitative survey I conducted revealed two consensus pop hits that had come out after February 24th. In my view, they represent two possible strategies for Russian entertainers—and perhaps culture in general—during the war.

The first one is Po baram (Around the Bars) by singer Anna Asti, formerly part of the duo Artik & Asti, whose songs often successfully brought together the main market trends from Soviet nostalgia to hookah rap. The solo incarnation has followed the same strategy and even has a concrete reference—Svetlana Loboda, who is no longer in Russia and won’t be soon. Bouncy house beats, red latex, sexy curves in the video, an elegant gender twist in the lyrics: a girl singing about a breakup, but it’s him who suffers, not her. Everything is familiar, but without the wildness intrinsic to Loboda; and of course, you couldn’t tell at all that the song was sung in the summer of 2022. (Indeed, another big hit contender—Malchik na Badu [Boy in Badoo] by Byanka and newcomer VESNA305—follows almost exactly the same template, aside from different sound references.)

In other words, this is a pure “ignorance is bliss” strategy. The fact that Asti herself comes from Cherkasy, a major regional city in Ukraine—which was shelled during the war—adds a special infernal surrealism.

The second hit is the song Ya russkiy (I'm Russian) by an artist who calls himself SHAMAN (given everything that follows, the cultural appropriation even in the name is symptomatic—there were no shamans in the Russian tradition). This is of course a much more vivid case—it is the position of “something happened, and we’re proud of it.”

The career of SHAMAN (his real name is Yaroslav Dronov) is indicative in itself. A contestant on not one, but two music reality shows, he first appeared on the radar in the fall of 2021 with the song Uletay (Fly Away), a post-chanson breakup track based on a hip hop beat, the chorus of which is taken from the composer Borodin that was clearly made for TikTok (and succeeded). Just six months later, everything changed. A day before the start of the war, SHAMAN released Vstanem (Stand Up), a patriotic slow song about ancestors who fought in World War II. And then followed it up with Ya russkiy.

One has to admit that from the standpoint of pop flair it is very viable: soulful versus combined with a powerful chorus, which gets in your head no matter how much you resist. The song is built entirely on confrontation: “I don’t need anyone else;” “you can’t break me;” “I go to the end;” “let the world burn.”

What is more interesting, however, is the question to whom these ambitious statements are addressed. The audience of the song—other “Russians”—is shown in the video as a faceless crowd with tricolors, whose main function is to celebrate the performer; especially telling is the visual parallel between people and ears of corn that is accented several times in the video—clearly both will be cut down when they ripen. Later, a minute and a half before the end of the video, the song itself ends and the afterword begins. First, we are shown an expensive car driving along a California highway in which two African Americans are jamming to the SHAMAN hit, followed by a spaceship in which animated reptilian aliens are dancing to the song.

Why? What is the point of this ending? In my view, this is basically the same story as Putin's lesson to schoolchildren, when he said: “Everyone believes that some kind of aggression is coming from Russia today.” The main targets of this message, “his people,” are not part of “everyone:” at least from Putin’s point of view, “his people” don’t believe that aggression is happening, but rather they share his views, support him and so on. When talking to “his people,” Putin doesn’t address them, but “everyone,” the people who don’t understand anything and must be persuaded (this thesis has been well developed by Meduza journalist Dmitri Kartsev). His people—who theoretically should be united and inspired—are just ears in the field, working material; the real audience is strangers, others, “everyone.” Ultimately, the lyrical hero of SHAMAN also addresses them—and demands love from them.

But of course he intends to get that love by force. In this sense, the key words in the song are “my blood is from my father.” In this inherently absurd line, obviously invented for rhyme, a harsh patriarchal reality shines through, where love and recognition are achieved through cruelty, through a belt, through spanking. Where respect is the right of the strong. Where liberation is submission.

Honestly, I no longer think that we shouldn’t be shy about this.

The author wishes to express his gratitude to the creative team of Don’t be shy, as well as Nikolai Redkin and Nina Nazarova personally.