On March 17, the International Criminal Court issued a warrant for the arrest of Vladimir Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, the Russian commissioner for children’s rights, for the unlawful deportation and transfer of Ukrainian children from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation. TV Rain correspondents Sonya Groisman and Nigina Beroeva looked inside the system of the unlawful deportation of Ukrainian children. They spoke with the children, their parents and guardians, as well as their temporary foster parents in Russia. Holod presents a digest of the report.

They talked us into evacuating because of the bombing. And then they took the children away because they had been registered as residents of a military base.

Before the war, Yevhen Mezhevyi and his three children lived in Mariupol. His wife left the family before the youngest daughter turned one. Yevhen worked as a crane operator at a factory, but in February 2022 he opened his own business—a fast food cafe. A couple of days after that, the Russian army attacked Ukraine.

Yevhen says that every morning after the war began, he would set the alarm clock for 4:45am, because air strikes would begin at 5:05am every day. After the alarm clock went off, the family had time to hurry into the hallway. Later they moved to the basement. They spent more than a month there without electricity, heating or water.

The shelter where Yevhen and his children took refuge was in the part of the city quickly occupied by the Russian army. But the well where he had to go to get water was controlled by the Azov Regiment soldiers. While the Russian military told the residents of Mariupol to wear a white armband not be targeted, the Ukrainian military argued that no armbands were necessary because they would be a symbol of the “Russian world” supporters.

“This was probably the most difficult part—figuring out where the middle ground is, figuring out when to take this armband off and where to put it on. You think: if I take the armband off now, the Russians will shoot me. But if I put it on—our guys will shoot me,” Yevhen recalls.

According to him, on March 7, Russian soldiers came down to the shelter and told them that there would soon be a mopping-up operation in the area and that they needed to evacuate from the city immediately. Yevhen and his children made it to the nearest Russian checkpoint, where the man was detained after his documents were inspected. He was in the military as a professional soldier in 2016—since then, the whole family had been registered as residents of a military base.

“They got fixated on the residence. They said: ‘You're ours now, so look for someone to leave the children with, and you'll go and explain why you've got those documents.’ I asked if it was going to take long. I was told that it could be two hours as well as seven years,” says Yevhen. He put the children on the evacuation bus, and handed Matvii, his eldest son, a bag of documents, phones and things he wanted to keep. “I wanted to give him my cross. But he said: ‘Dad, it's better if it guards you.’ And they left. The Russians took the cross off before long,” Yevhen says.

Matvii recalled that he and his sisters were held at a temporary accommodation center for two weeks, and later transferred to a hospital. Then he was taken to Donetsk.

At this time, Yevhen would be transferred from one prison to another, where he would be tortured, interrogated, and beaten. “They asked me if I had killed Russians,” he says. “And how could I kill them if I hadn't even been in the ‘ATO zone’ (Anti-Terrorist Operation Zone, the term used back in 2016 to distinguish the territory of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions under the control of Russian military forces and pro-Russian separatists—ed. Holod)? [One of the interrogators] grabbed me by the neck and hit my face against the bars, then they started kicking me in the stomach. They were beating me quite hard.”

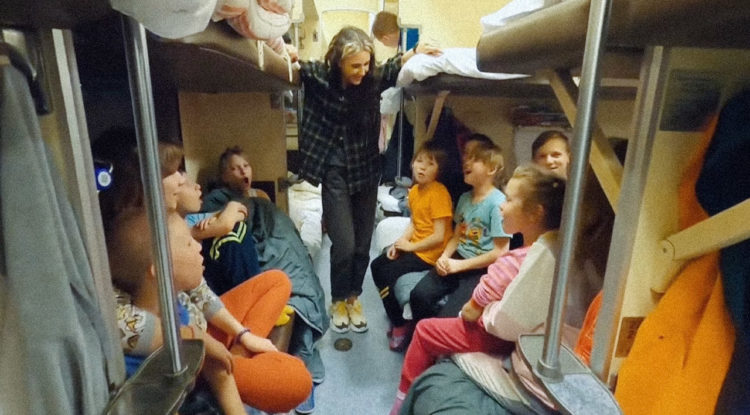

Yevhen later ended up in the Olenivka detention center for Ukrainian prisoners of war. And his children, after several weeks in Donetsk, were sent to a camp near Moscow.

The children are deported from Ukraine. In Russia, they are placed in temporary accommodation centers or orphanages.

According to the Ukrainian authorities' calculations, 16,221 children were deported from Ukraine to Russia in a year. This includes orphans who were removed from boarding schools and orphanages, as well as those missing after bombings and evacuation. Some of them may have died, but their relatives continue to hope that their children are alive and only just removed from Ukraine.

As the TV Rain correspondents report, the human rights activists roughly classify the removed children into three groups. The first group is children who have relatives and guardians, such as the children of Yevhen Mezhevyi: it is known who their father is and where he is. The second group is orphans who were removed from the occupied territories of Ukraine in 2022. The third and the largest group is the children from boarding schools in those parts of Luhansk and Donetsk regions that have been controlled by Russia since 2014.

Ukraine describes this as deportation of the children. Russian authorities call this “saving them from war,” omitting the fact that it was Russia that made the evacuation necessary.

By the time the report came out (February 26, 2023), 307 children had been returned, according to the Ukrainian authorities. How many hundreds or thousands of children now remain in Russia is unknown.

The children's evacuation from the territory of self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics began a few days before February 24, 2022. At that time, children were taken to Rostov region. The Ukrainian authorities do not have lists of these children. Before 2017, Ukraine had managed to remove most of the children from orphanages to the safer territories. But since then, orphanages had been filled up again, and these children were the ones sent to Russia in 2022.

Further on, as more territories in Kharkiv, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Luhansk, and Donetsk regions were occupied, children were moved by entire institutions. Their employees, as well as the doctors from local hospitals, managed to save some children from deportation. They hid them in hospitals, faking the medical records to show that the child's condition was not suitable for relocation. Some of the orphanage staff placed the children in their own homes.

The TV Rain correspondents say that the Russian military view children from the occupied territories as a trophy or as something to be captured and brought away with them. Once in Russia, children would be placed in temporary accommodation centers or sent to orphanages.

They change the citizenship of the children and then “reeducate” them by means of “military-patriotic” trainings

TV Rain obtained correspondence between officials from the Ministry of Education and the heads of regional child protection services. It became clear from this correspondence that the children were located all over the country, from Stavropol to Bashkortostan. “We have counted at least 24 institutions, but there are clearly more,” says TV Rain correspondent Nigina Beroeva. “That's because the Moscow and Leningrad regions were not reported in that correspondence.”

One of the boarding schools where children from Ukraine were located says on its social network accounts that on February 23, Defender of the Fatherland's Day, the children took part in “patriotic” events. They were watching a briefing by the spokesperson for the Russian Ministry of Defense. At another boarding school children were making trench candles for the front. In a third one, the pupils went to a military hospital to visit and congratulate the soldiers wounded in action in Ukraine.

“Such ‘military-patriotic’ training is going on in 21 of the 24 institutions where we have evidence orphans from Ukraine were definitely sent,” says Sonya Groisman, a TV Rain correspondent. “It's letters to soldiers, assembling assault rifles, activities to any taste,”adds Nigina Beroyeva—“for many children, [a placement in] a boarding school is temporary. But at the same time, many [then] will be placed with Russian families.”

In Russia, the legal procedure for adopting a child from another country is complicated. It is necessary to contact the guardianship authorities of another country and to make a lot of various inquiries. Then it is necessary to get confirmation that no one in their home country is going to be a guardian, and that the government agrees to transfer the child to another country. There is no way to exclude these rules from the process. But as it turns out, there is no need to, if you simply give Ukrainian children Russian citizenship.

As early as May 30, 2022, Putin signed a decree to allow the orphans from the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics, as well as from Ukraine’s other occupied territories, to be granted Russian citizenship on a simplified basis. And since September 27, 2022, when the results of the so-called “referendum” in the Russian-occupied territories were tallied, children can receive Russian citizenship automatically, according to Russian law. This violates the Geneva Convention, which states that the occupying state must not change the children's citizenship.

“This will be the topic of investigation by the International Criminal Court. Elements of genocide could be proven. Given the decree that Putin signed, his personal guilt could be proven as well,” said Alexandra Romantsova, executive director of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Center for Civil Liberties. (As of March 2023, Putin, as well as Maria Lvova-Belova, the presidential commissioner for children's rights, have warrants of arrest issued against them for the unlawful deportation and transfer of Ukrainian children from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation—ed. Holod).

Ukrainian children are being forced to change their identity to Russian. In international practice, this is considered violence

According to Lyudmila Petranovskaya, a Russian family psychologist who has been involved in foster care of orphans for years, there is an important principle in the international practice: if a child has an identity—a national, a religious or other—they are not placed in a family that has a negative view of this identity.

The Hague-accused commissioner, Maria Lvova-Belova, has herself adopted a 15-year-old boy from Mariupol. She has been “rescuing” Ukrainian children the whole year. Lvova-Belova is married to a priest, they have five children of their own and four adopted. She used to be a senator in the Federation Council, and is currently a member of United Russia party and the Russian children's ombudsman.

In one of her public appearances, Lvova-Belova said that children in Ukraine had been indoctrinated with anti-Russian attitudes. As an example, she cited a group of children brought in from Mariupol: “They spoke negatively about the [Russian] president, said all sorts of nasty things, sang the anthem of Ukraine, said ‘glory to Ukraine’ and all that.” According to Lvova-Belova, all the parents of these children from Mariupol abandoned them: although this particular group included the three children of Yevhen Mezhevyi, who was arrested during the filtration.

As TV Rain found out, the most difficult teenagers are “reeducated” in Chechnya. There, a program of “military-patriotic” and “ethical and moral” education has been prepared for them.

“The aim to reeducate children somehow, to convert them from love for Ukraine to love for Russia, is an act of violence, and quite a cruel one,” Petranovskaya says. “The child is forced to give up what is important and valuable to them and choose something else. It's probably less painful for young children because it's not part of their identity yet. But for children older than ten, it can be very painful.”

Decisions to approve adoptions are made within a day. The child welfare agencies are literally forcing the foster parents to take the children.

All of the foster families interviewed by TV Rain describe that the child protection services would rush to place the children in a family as soon as possible. One of the foster parents, Stanislav Tokushev, recounts: “We were given very little time. They sent us [the children's profiles] in the morning and asked about [our decision] in the afternoon. Everything was decided in just one day. Apparently, it had to be done as soon as possible. There must have been a deadline or something”.

“[It's] like a mobilization here. I got a call [and was told that] in a week [I had to] pick the kids up. How can I pick them up right away when I have to prepare stuff [to do it]? To be honest, it was already the limit for me, so it was hard,” Larisa, an adoptive mother from Novosibirsk who is raising seven children, told the Novosibirsk-based publication NGS.ru.

Lvova-Belova said that each child had the opportunity to choose from three or four families after viewing the video profiles of the families and videocalling them. “Some children chose a family because there was a doggie, and some because the mom is pretty,” Lvova-Belova said.

The reality differs from Belova’s claims, however. For example, Stanislav Tokushev, the adoptive father, told TV Rain that he had never even heard of any kind of a video presentation.

The main form of placing Ukrainian children in Russia now is temporary guardianship or placing them with professional foster families. In other words, the state is hiring parents and paying allowances to them. But Lvova-Belova has stated that temporary custody can become permanent once the children become Russian citizens.

Petranovskaya explains that in the international practice, in a situation of military conflict adoption should be absolutely forbidden: “When a child is adopted, they are legally equal to a biological child. They can have their name and surname changed, as well as their date of birth. And after the war, the relatives may never find him or her again.”

Russian authorities do not cooperate with the Ukrainian ones. Children are simply being stolen.

Lyudmila Petranovskaya says that in the current situation it is necessary to look for the children's relatives as quickly as possible, and it would be more correct for the Russian authorities to cooperate [with the Ukrainians], despite the ongoing hostilities. “If possible, it is necessary to return the child to the environment where there are people close and familiar to them. But this is clearly not being done—or not being done enough,” Petranovskaya says.

Aksana Filipishina, a human rights activist and a representative of Ukraine's children's rights commissioner, told TV Rain that back in June she asked Lvova-Belova to start this process. But so far the request has remained without an answer.

Yevhen Mezhevyi from Mariupol, who was separated from his three children during the filtration, was released a month and a half later. His son Matvii said that by then he and his sisters had already been offered to go to a foster family. “But I said that I wouldn't give an answer until I informed my dad and talked to him. They insisted that my dad wouldn't have time to arrive so fast, we had to think sooner,” Matvii recalls. He was able to call his father, who told him not to go to the foster family under any circumstances.

With the help of Russian volunteers, Mezhevyi was able to come to the Moscow region and take his children back. “Why are Russians adopting them? Don't they have children to take care of in Russia? Don't they have enough children in orphanages? Why don't they take care of them instead? Each of the Ukrainian children has their relatives. They say that these children are orphans. Are my children orphans, too? There could be thousands of such stories,” says Mezhevyi. “They should have just stayed away from us. If they had left us alone, no one would have died, and our children wouldn't have to be adopted. What are these ‘kind gestures’ for? What do they want to show?”

Not counting those children who have been removed from Ukraine, there are currently about 30,000 children in Russia's orphan database.