In March 2022 anti-war rally broke out on the streets of Russian cities. As the Ministry of Internal Affairs claims, 3511 protestors across Russia have been detained, 1700 of them in Moscow. The 26-year-old artist Alexandra Kaluzhskikh was arrested on March 6th at an anti-war rally in Moscow and brought to a police station in the Brateyevo district where she was interrogated and tortured in the process, as were some of the other detainees. Kaluzhskikh managed to record an audio of what was happening with her phone—the recording became viral in Russia. Holod spoke with Alexandra about the violence she experienced at the station—and also the violence she experienced at her own home as a child.

(AK for Kaluzhskikh, M for a male police officer, F for a female police officer)

F: How did you know about the rally?

М: Shouldn’t you care just a bit about yourself?

AK: (sighs) I refuse to answer.

F: Shit, what are you doing this for?

AK: Article 51 (Article 51 of the Russian Constitution guarantees the right not to testify against oneself or one’s close relatives.—ed. Holod).

F: I don’t get it either. You are fucked in the head. You are fucked in the head.

AK: So a man is beating me right in front of you and I’m the one fucked in the head?

F: Yes, yes!

М: We should have that electric thingy here.

М: Yeah, fingers [unintelligible].

F: You fucking live in this country.

AK: Are you talking about tasing me?

М: Yep.

М: 220 [volt], will have to [unintelligible]

Holod: How are you feeling now?

Kaluzhskikh: I wasn’t able to think clearly for a few days, had others hold my hand. Now my head seems to be getting clearer.

How did you get detained?

On Sunday, March 6th, I arrived in downtown Moscow, Komsomolskaya metro station. There were a lot of people and even more policemen. They stopped people randomly and searched their bags. I heard about people having their phones and chats checked but it didn’t happen to me. I walked a bit, saw my friend in a group of people, many girls, and joined this group walking down Kalanchevskaya Street. Then the police split this group into two parts, one managed to turn into side streets and leave and the other was surrounded. Policemen didn’t introduce themselves, didn’t say “you’re under arrest”, didn’t tell us what we were arrested for. We didn’t put up any resistance. None of the people around me had any posters or chanted anything, we were just walking together.

When they surrounded us, they searched everyone and put us in a line to board a riot van. All this time they were shouting and calling us names. Treated us rudely, like some kind of criminals. Eventually they pushed 29 of us into the van, there was a very small compartment with benches. We shouted: “Bring another van please!”. It was unlawful, nobody is supposed to stand in a police van.

What happened when you were brought to the police station?

They [policemen] took our IDs, copies of IDs, and led us one after another into a meeting room. We spent about two hours there. Everyone had water, snacks, and pop-its. One police officer saw a pop-it [in rainbow colors] in my friend’s hands and asked: “Are you from LGBT or what?” She’s like: “I’m from Moscow. Wanna try?” He says: “No, I’m good.” She says: “Well, I’m not.” Then they put up a siren and announced the “Fortress Plan”.

“Fortress plan” is a code name for a special protocol, which is supposed to be used by police stations in emergency situations; in practice, “Fortress Plan” is often used when mass arrests are made to temporarily prevent detainees’ contacts with the outside world and lawyers in particular.—ed. Holod.

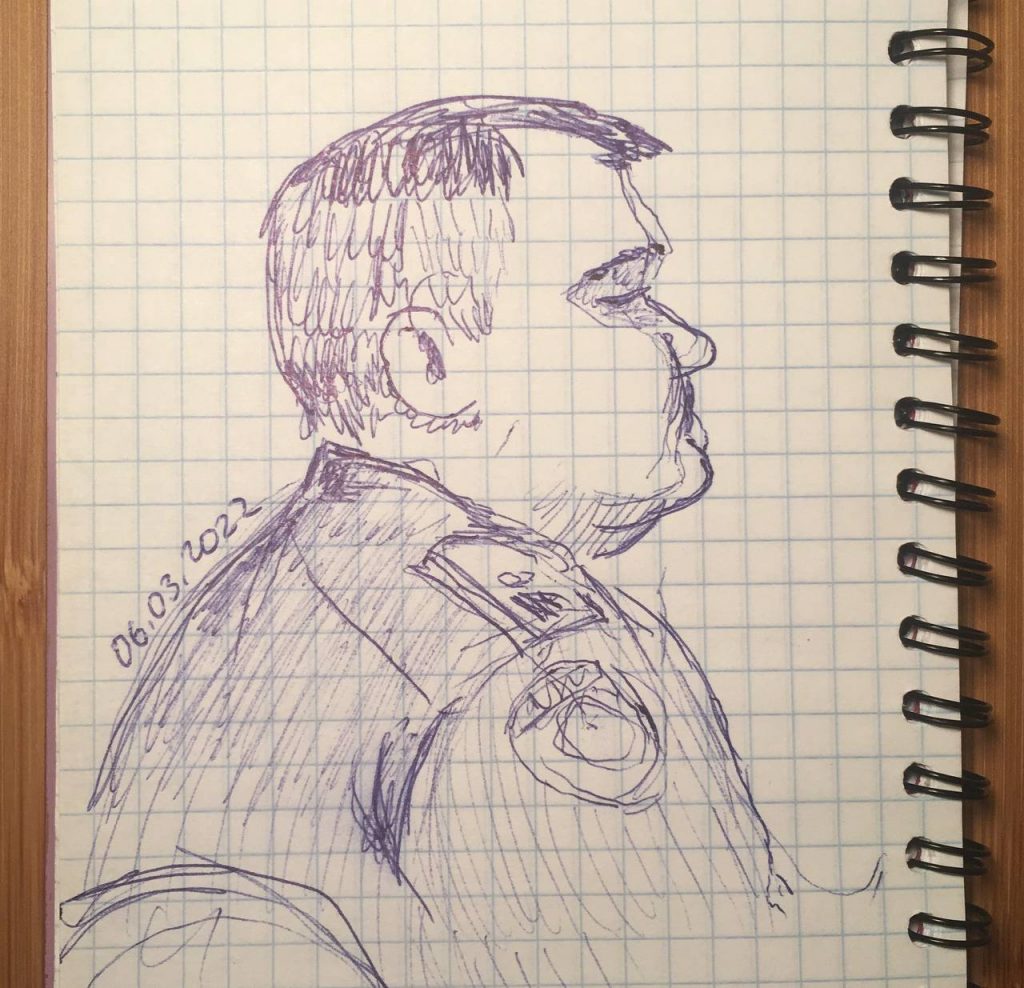

We felt very optimistic. I am an artist, so I drew some sketches of cops. Made two beautiful portraits. Those were good [cops], they didn’t beat us. Maybe they had a hunch we were being beaten but they didn’t take part in torture directly. Just told us very seriously to turn off our phones. Compared to what happened later in that special room, that was a walk in the park, in my opinion.

After a while, they began taking us to a place where they took photos, two or three of us at a time. This place was across the cells. There was this little cop with a camera, he goes: “Stand against the wall.” I say: “No, I’m not gonna let you do that.” He says: “Come on, this is our standard procedure.” [I objected again and] he asked what article [in the laws] I was referring to but I didn’t remember, I only knew that this was not mandatory. But he couldn’t refer to anything either, they just had this “detention protocol.” They always did this but didn’t even know why. Just the way it is. I and another girl in our group refused, and the third one agreed. They pressured us to agree, so “it would be faster.” And they didn’t lie: everyone who agreed to do everything they asked was indeed “processed” quickly.

What happened to those who refused to have their photographs taken?

After we refused about ten times or so, they took the two of us to a separate corridor, which turned out later to be next to the torture room, No. 103. Some man was passing along this corridor and he called us “special contingent”—I guess this means torture contingent.

I had two phones on me because I knew they could take one away, and then I wouldn't be able to report to OVD-Info (a Russian NGO providing all kinds of assistance to detainees at rallies, informing relatives and the public about their names and numbers, coordinating legal assistance, etc.—ed. Holod). I was afraid, so I took another phone with this in mind. I had no idea that it was to serve a completely different purpose. So I had a dummy phone, an old Lenovo which I never use, and my regular phone. While we were sitting in that corridor and waiting, I heard screaming from one of the rooms, so I started recording when I was still in that corridor. I put the real phone in my pocket and held the dummy one in my hands.

What did you see when you entered this “special room”?

There were four people there. Two desks by the window, facing each other, like in any government office, with two young women in police uniforms. A brunette to the left and a highlighted blonde to the right, a bit squint-eyed. The girls were asking questions, filling in forms. And the men… One was wearing a black turtleneck, he was the one doing all the torture, beating and other dirty work. The other one was just standing there leaning against a cabinet. He called me names a couple of times but did nothing more.

When I entered the room I thought it was funny: there were two spotlights facing the door like in some real-crime series. I remember thinking, “Wow, these guys have been watching too much TV.” I thought it was such a stupid frightening tactic.

(AK for Kaluzhskikh, M for a male police officer, F for a female police officer)

М: Get up, she will take a picture, and off you go.

AK: No, I refuse to be photographed.

М: No, you’ll have to.

AK: No, I won’t. [sounds of blows]

М: Come on, come on.

AK: Go ahead, beat me some more.[unintelligible]

М: Get up, get up. [sounds of blows] Go and stand over there.

AK: I will not stand over there. I refuse to be photographed. I will sign my refusal to be photographed.

F: Go [unintelligible].

М: That’s it, you don’t have a phone.

AK: So you won’t even write up a seizure report?

М: Why would I need a seizure report?

AK: You just broke the screen…

М: Just happened.

AK: It just fell on its own, right?

М: When you were entering, you just slipped…

М: Three witnesses.

AK: Thank you. Оh, you didn’t even break it, thank you.

М: Get up.

When I entered, they snatched away the phone I had in my hands, unblocked the screen and checked it. Guess they were relieved and threw it against the wall. You can hear in the recording that it bounced but didn’t break. They didn’t notice the other phone in my pocket, although they did look at other girls’ pockets, it was pure luck. They didn’t do to me a lot of things they did to other girls. It’s like torture was customized: some were yelled at and threatened, I [later] read that one girl was choked with a plastic bag. Approaches must have varied but we were all tortured by the same man—black turtleneck, gun holster.

What questions were they asking?

The women were asking about our place of employment or study, phone number, actual address. So one of them is asking one of these questions, I say: “Article 51” (Article 51 of the Russian Constitution guarantees the right not to testify against oneself or one’s close relatives.—ed. Holod). Then the man kicks me. I was seated, and he just kicked me on my legs as hard as he could. I had bruises later.

Then there was a very hard cuff on the back of my head, as hard as he could. I said: “Wow, but my father could do harder.” Each time I said “wow” or “fuck,” I was just fucking shocked by the fact I was being beaten, that actual blows were landing on me. So each time I say this on the recording, that means I am hit and I just have no idea how to respond.

They asked the same questions over and over. I said the same thing, and every time he would hit me. Then he poured some water on me, and I made a comment about my tits, “please don’t stare,” because water [got onto my breasts] and the T-shirt was sticking. They started talking about my tits.

(AK for Kaluzhskikh, M for a male police officer, F for a female police officer)

AK: Wow!

М: Yeah!

AK: Holy fuck! My father could do harder though.

М: Shall we go on?

AK: (sighs)

М: Or is it Article 51 again? (Article 51 of the Russian Constitution guarantees the right not to testify against oneself or one’s close relatives.—ed. Holod)

AK: Ladies, are you OK watching this?

F: Place of study… We’re OK. Are you OK going to rallies?

М: We are not OK watching this.

М: Look at your fucking tits, floppy like a fucking cow’s. Look at your fucking self. Fucking monkey.

After that they began beating me with the half-empty plastic water bottle on my face, my head and my body. And my comments on these hits were for the sake of the recording. He hits me, and I’m like “wow, he hit me on my face with a bottle.” I kept saying this to have this all documented. Then he grabbed me by my hair and started pulling me in all directions. There is noise on the recording because the phone was in my pocket. This was when I said “it hurts, it hurts.”

How long did it all last?

About ten minutes, I think.

When did they stop?

I’d say “Article 51”, they didn’t like this answer but they didn’t achieve much. My phone and my photograph were super important for them, so I’m happy they didn’t get either after all.

The brunette wanted to take a picture of me with a small old point-and-shoot. She stood up from her desk and approached me saying “now we’re gonna go and have your picture taken.” I said: “No, I refuse,” and pressed my hands against my face. They say: “You’ll have to,” I say: “No, I won’t, I’ll sign my refusal.” And they got off. They forced some girls, put them [against the wall], [pulled] by their hair. But I'm stout, big and tall. They either thought they wouldn’t be able to or just decided not to. I have no idea of their logic.

I can also tell you what really hurt my feelings. One of the women asked me: “Are you fucked in the head”? I asked her myself: “So a man is beating me right in front of you and you’re saying I’m fucked in the head”? “Yes.” Not sure why but this just broke my heart. No one in that room, either men or women, had even a drop of sympathy. They didn’t see me as a human being. They saw some kind of animal, an enemy. I was completely dehumanized for these people, deprived of my human nature. I cannot imagine committing such acts of violence against anyone. For them, it was routine.

How many times were you hit?

About ten, I think, maybe more.

I really want to comment on what I said about my father. When I entered that room I had a defense response. These insults, blows, it was exactly like when I was a kid, and my father would humiliate and spank me. So very familiar, you know. My defense response has been forming for many years. You know you can’t cry because you’ll be [hit] only harder.

At what age did this violence occur?

From my early childhood until my mother divorced him and we moved out. I remember very well being beaten with a belt when I was five years old. I would huddle up and he would just hit wherever he could reach.

Then beatings stopped but there were pokes, insults: “cow”, “idiot”, “shithead.” He would often say that I needed “all this crap beaten out of my head.” Just like those cops. He went to a military boarding school. I think this is something they share, this military stuff. Because men go through this repressive system, too: they are humiliated so that they then become part of the system. They probably learn these tactics and then reproduce them.

When I was 17, my mother and I finally moved out, but my father has been harassing us for a long time after that: broke into our apartments, knocked our door lock out with a hammer, cut electric power. I have younger sisters, and he was more interested in them and our mother. At some point he lost any interest in me and stopped following me.

I am now 26, and I haven’t been in touch with him since 2016, but I am still coping with all the consequences. I have complex PTSD, flashbacks, triggers and, thanks to those cops, new triggers and flashbacks now. My brain must have turned the defense response on at that moment, this is why I managed to sustain the way I did. For the first couple of days I really didn’t care, I wasn’t feeling any consequences.

I wouldn’t have been able to just start crying in that room. This is forbidden [for me], this is not the way my body responds. I burst out in tears when they took me to another room.

Did this woman in the room remind you of your mother? Is this why her reaction hurt you so much?

Shit, now I’m gonna cry. You’re spot on, I think. That’s why it was particularly painful. My mom suffered from my father, too, and tried to soothe [my sufferings], I think. She would always try to get me to school instead of him, find some loopholes, shield me [from him]. On the one hand, I understand that she was a victim in that situation, but on the other, I kept thinking: “Mom, why didn’t we leave him earlier? I have been waiting for this divorce all my life but it only happened when I grew up.”

This was like a copy paste from all these childhood situations. My mom did not believe that it was OK, of course, but she never tried to stop him directly. You kind of expect some solidarity from a woman. Then I thought that this woman had seen a lot of such beatings, and she is a cop first and foremost.

How did it all end in that room?

— They let me out and brought to another room with several cops and several girls, probably after the torture room as well. I was seated next to a cop who was kinder. Another one was tougher, he was shouting at the girl next to him. The one with me was super kind. He had a caring tone and wasn’t trying to strong-arm me. So I sat there sobbing and crying, feeling sorry for myself.

Did you feel pain?

I don’t think I was feeling anything physical at that point. Later, when the tension was off, I felt that everything hurt. [At that point] I was thinking of myself in the third person, the reality was catching up, [I was beginning to realize that] something terrible had just happened to me.

They were telling me there was nothing to cry about. I didn’t respond, just started crying even more because of this devaluation and gaslighting.

The cops were telling you there was nothing to cry about?

Yes, the one sitting at the desk and processing another girl. I was crying, and this girl put her hand on my shoulder. It felt so good. I took her hand and I felt that I was not alone.

What happened next?

The cop gave me several papers. I signed the ones that the detainees’ guide [compiled by OVD Info] said it was OK to sign. Then they brought me back to the large meeting room. There were four or five people there, including my friend. I started frantically sending my recording to everyone I could, asking whether they could hear it well. I suffered so much and now wanted it not to have been in vain. It would have been very sad if you couldn’t hear anything.

When they called for me to sign the detention report, there was this round-faced cop, the one I drew a portrait of. He told me to sit down, with a bit of aggression. And then I started asking him what this line meant, what’s gonna happen if I sign that, and he began warming up to me. I told him I was an artist and drew a portrait of him. And this is when he became very warm to me. He told me like he was talking to a child: “Sure, go get your notepad, show me.” In a bit of a fatherly way. I brought my notepad, suggested he take a picture of his portrait as a souvenir. When I did that, even his face changed, he was genuinely delighted, he smiled and took pictures of his and his colleague’s portraits.

I had my friends waiting for me outside. One of them had been waiting since the time we were in the police van. She went to Brateyevo right away and spent several hours in front of the station with a parcel for us. I hugged everyone.

I was receiving calls and messages from journalists, activists, all kinds of people. I couldn’t think clearly and just rode an “OVD taxi” [volunteer drivers organized by OVD Info to take released detainees home.—ed. Holod] home.

I had headaches, suspected concussion, but I refused to go to a hospital because at that point I had no traces and I was too tired. But on the next day bruises transpired, I had a small black eye. I took pictures and had it all written down in an ER. For the first few days, my friends have been doing everything. They took me to the clinic, fed me, told me where we were going, called cabs, posted on my social media, asked for support. I am trying to raise some money.

Do you have legal support?

We have a lawyer, same person for all the girls who were tortured.

Are you planning to bring these people to justice?

I sure am. I will do all I can to find them and sue their asses. I will do everything, I will defend myself in court, I will file a complaint with the Internal Security Office (department of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs responsible for investigating misconduct and crimes perpetrated by police officers.—ed. Holod).

Of course, I am not managing too well on my own but I have great friends who are helping me with every step. As a kid, I didn’t have any support, I felt very lonely, I had to keep my pain inside and manage it however I could. But now I have a huge network of my friends, journalists, [social media] subscribers, activists, human rights defenders, lawyers, therapists and psychologists. I received a huge amount of help and am trying to share it with others. I am not alone. I am going to be fine.

I don’t think that a cruel punishment for those who cruelly punished others can break the cycle of violence in our country, so I would like to see some rehabilitation programs for abusers and cops. I would like us not to be part of this cycle, not to multiply violence, beating them in revenge for having beaten us. And I am not sure anything good awaits them in jail if they get there… If we are ever to see a bright future, the ideal future as I see it, there will be rehabilitation centers for both abuse victims and abuse perpetrators in families, in the government, in all kinds of institutions.

I would like to see support offered to such people, too, to help them overcome their aggression and their pain which they now pour on others. So that they become more productive members of the society rather than the types they are, beating young girls without a drop of remorse.