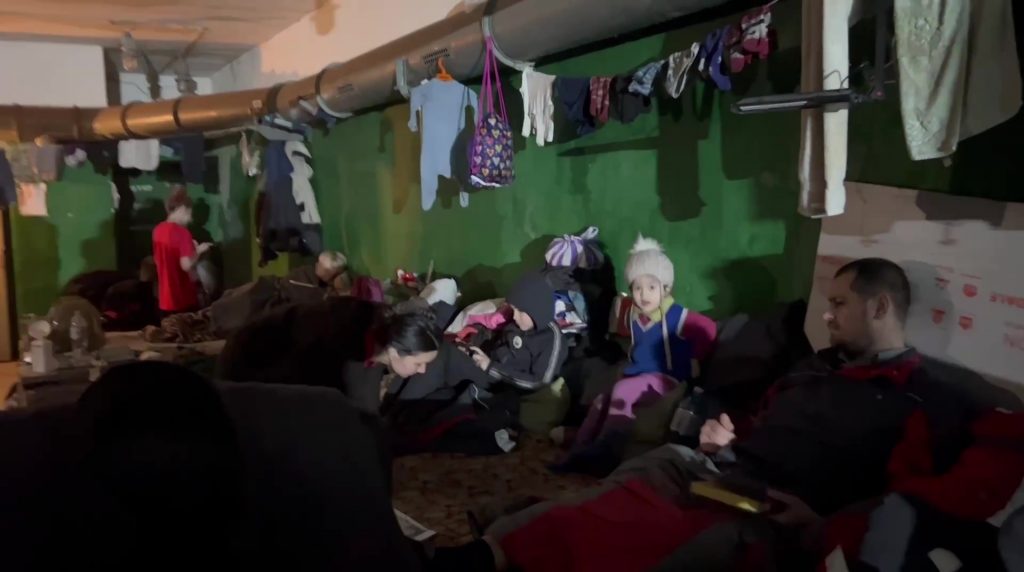

Russia’s 70-day siege of Azovstal steelworks, the last bastion of the port city of Mariupol in eastern Ukraine, approached a bitter end in early May after the last Ukrainian troops holed up inside surrendered to pro-Russian forces. Until May 7th, when the last were evacuated, hundreds of Mariupol residents—women, children and elderly people—had also been hiding in bomb shelters beneath the steel plant. They suffered hunger, loss, pitch-black darkness in the endless corridors of the plant, and survived to tell their stories.

On March 17th, 34 people—Azovstal employees and their families—sat down at a table to party: Evgeny, a mill operator at the plant, turned 35. They scrambled together some treats: canned meat with cereal and sweets from the plant cafeteria. There was some moonshine, distilled from hand sanitizer in a self-made contraption assembled from a steel boiler and two buckets. The kids were given paper and pencils, found in plant offices, so that they could draw a happy birthday poster.

By that time Evgeny, his colleagues and their families had spent almost a month in a bomb shelter beneath the Azovstal rail and beam shop.

As his present, the birthday boy received a vial of perfume, which someone had shoved into a bag while packing for the shelter. As soon as the birthday chanting began, Evgeny’s colleague Andrey Vodovozov (his last name was changed at his request.—ed. Holod) recounts, lights went off, everything around them began shaking, with pieces of concrete falling down from the walls and the ground moving under their feet.

Fighting for Mariupol began the day after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This city, in the words of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, became “the heart of the war”. Russian and Donetsk People’s Republic’s (DPR) forces blockaded the city almost entirely by mid-March, cutting off the Ukrainian authorities’ ability to evacuate civilians and bring humanitarian aid to the city. According to Ukrainian official figures, 2357 civilians had been killed in Mariupol by then; however, city authorities claimed that this figure was only a “small handful”, and that the actual number of casualties was in the tens of thousands.

Andrey Vodovozov, a 31-year-old Azovstal electrician, found himself in a bunker under the plant on February 24th, the day the war began. In the morning he went, as usual, to work, but this time he took his whole family with him: his wife, his two-year-old daughter, and his dog, a samoyed named Maya. That day gunfire had already been heard in Mariupol, and Vodovozov decided that his family would be safer in the shelter under the plant. At that moment he thought that he was taking his family out of the home “for a week at the most”: he was sure that the conflict would not last long.

He left his family in a bunker and with his colleagues he went to close the shop where he had worked for four years: to cut the electricity in the equipment, to turn off the light in the rooms on military orders, so that they could not be seen from the street.

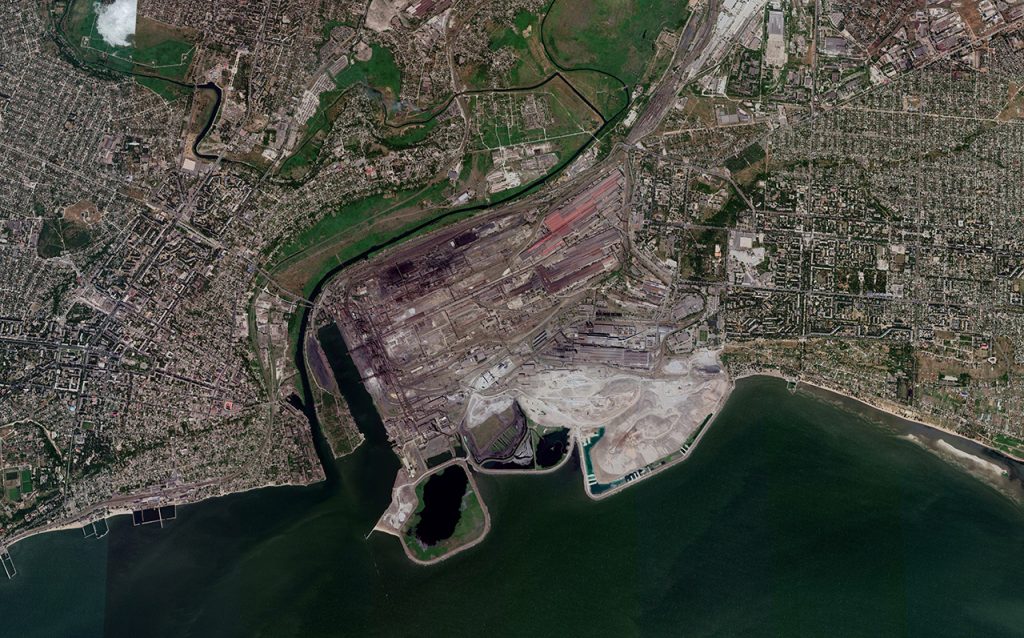

Azovstal is a huge metallurgical plant. It occupies an area of 11 square kilometers—a fifteenth of the entire territory of Mariupol. In an interview in mid-May, the director of the plant, Enver Tskitishvili, called it “the most powerful ferrous metallurgy enterprise in Ukraine”. According to the plant director, almost 11 thousand employees were working there before the war. When counting contractors and their family members, about 40 thousand citizens of the city out of half a million were connected to Azovstal.

In August 1933, the plant began producing pig iron, or crude iron. During the Great Patriotic War (the term used in Russia to denote specifically the fighting between Germany and the USSR in 1941–1945), the plant was almost razed to the ground by German troops, who occupied Mariupol. The plant was rebuilt in the post-war years. Before the Russian invasion in February 2022, Azovstal was one of the leading Ukrainian steel mills: in 2020, for example, it produced 3.8 million tons of pig iron—18.6% of the country’s iron.

A system of bomb shelters—“an entire multi-story city” underground, in the director’s words—has remained under Azovstal since Soviet times. Until 2014, when the armed conflict in Donbas broke out, nobody thought that these bomb shelters would ever be useful again, Enver Tskitishvili told the BBC in early May.

But then employees pulled up the archives and saw that there were a total of 36 shelters for 12 thousand people at the plant during the Soviet era. And five of these bunkers, according to the director, are so strong that they could withstand a nuclear strike.

In addition to the bomb shelters, there are tunnels eight meters below the plant—some of them so long that they go from one end of the plant to the opposite. Azovstal executives cleaned up these tunnels over the years after 2014, and a week before the war with Russia they hid food and water supplies there.

“These tunnels themselves are not shelters, but their depth allows us to save people. And [after the Russian invasion] we made an announcement: ‘All people can come to us at Azovstal, we will feed and protect them,’” said the director of the plant. According to him, at the beginning of the war, plant employees even drove around their colleagues’ homes helping them get to the bunkers.

The plant turned out to be suitable not only for giving shelter to civilians. Surrounded on three sides by the river Kalmius and the sea, it became, as the director put it, “a very convenient and strong fortified point” for the Ukrainian military. Already in the first days of the war it took up defenses at the plant; according to the DPR authorities, at the beginning of April there were more than three thousand Ukrainian troops on site.

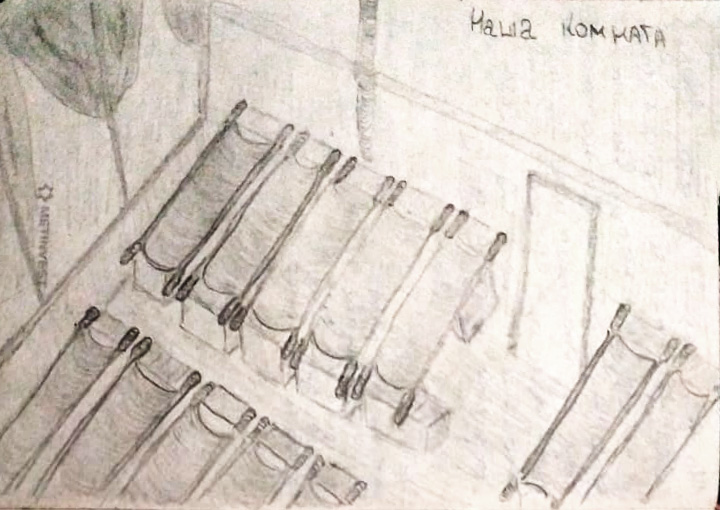

The shelter where Andrey Vodovozov’s family ended up was spacious—it could accommodate 300 people sitting on benches. But only 43 lived there, so it was possible to sleep not sitting, but lying down. “You put four benches together—that’s a great double bed,” he says.

Water was brought from the factory buildings: every summer the factory stocked up on bottles of mineral water so the workers would have something to drink in the heat. They were fed on dry rations, which were stored in a bunker. “It was great stuff,” Vodovozov says, describing the food. “Two porridges: pearl barley and buckwheat. A can of stew. And a lot of ‘paper’ crackers, as we called them. Every day we cooked soup for everybody from two ration packs. One potato and four pasta pieces per bucket of soup. If there was a piece of pasta on your plate, it was a feast!”

People ate hot food only once a day, at lunch. “Boiled water in the morning, boiled water in the evening, soup in the afternoon. It doesn’t taste as disgusting as you think,” Vodovozov laughs.

For tea, coffee, sugar and salt, he had to make forays into the plant: “You go and wait to make sure [the bombardment] doesn’t come, God willing.” Vodovozov describes his expeditions around Azovstal buildings, where he used to work: “For example, a missile blew up some duty room (the room where duty personnel sit and where tools are stored.—ed. Holod). You go into the duty room and you see that the drawers are open—well, great.”

The bunker inhabitants needed to go outside not only to get food but also to get some information about what was going on in the city. Vodovozov himself recalls climbing onto the roof of a factory building where he could clearly see his parents’ neighborhood—and watching their house burn down.

“There are no civilians at the plant”

At the end of March, when fierce fighting for Mariupol had been going on for over a month and the city was almost completely destroyed, the DPR officials said one of the last pockets of resistance by the Ukrainian military was the Azovstal plant.

On April 18th, Russian airforce, as claimed by Mariupol authorities, began dropping super-heavy bombs on Azovstal. Two weeks earlier, the Russian state news agency RIA Novosti (Russian state-owned domestic news agency.—ed. Holod) reported that the Russian and DPR militaries were “mopping up” the territory of the plant: “Heavy shells are bursting at the Azovstal plant. The artillery men’s hands are finally untied—there are no civilians at the plant.”

These shells were bursting right over the head of Anna Korchmina, a 35-year-old factory worker from Mariupol (her name and surname have been changed at her request). Since March 5th, she and her parents, sister, aunt and three-year-old daughter had been sitting in a bomb shelter under a workshop at Azovstal, which provided the plant with telephone and dispatch communications.

Her father sent her together with the child and her sister to the shelter when shells came very close to their apartment building. He stayed in the flat with his wife because he didn't want to leave his home. But a few days later, they too came to the bunker: a shell landed in their building, and the roof collapsed.

As the shells flew into the factory grounds, the ground “swayed under her feet”, Korchmina recalls. And when they fell near the bomb shelter, the metal beams with which the bunker was reinforced would begin to rumble deafeningly. “It was like being in a steel pot. Imagine having a pot put on your head and someone banging on it,” she says.

To her three-year-old daughter, who woke up in the night from bombing raids crying, she would say that there were elephants upstairs. “Elephants play soccer and fall down. They stumble, they can’t walk, and they have to be treated,” Korchmina says. “She's that age: she asks ‘why’ about everything.”

The bunker where Korchmina was sitting was deep underground. It was “absolute darkness”, she recalls, and at first people walked around with flashlights. Then they came up with an LED strip attached to a battery, and instead of darkness they lived in semi-darkness: “The lighting was just enough to avoid bumping into each other.”

The rooms in her bunker were cramped. Twenty-four people lived in one room with her, their bunk beds were next to each other. There were no real beds—the residents made their sleeping places themselves: they put two boxes and stretched a stretcher between them. It was very cold and damp to sleep on the stretcher, but Korchmina and her father managed to find some sweatshirts in the half-destroyed plant building and put them on the stretcher instead of the mattress. It became warmer.

Above Korchmina’s shelter was a basement with several flights of stairs. The residents set up a kitchen in one of them. Two hearths were built: they stacked bricks and placed a grate from a refrigerator on top of them. The pots and pans they had managed to take from their apartments were placed on the grate. The fire was started with pieces of chairs and storage pallets that had been brought in from the ruined city.

In mid-April—she could not remember the date because it was impossible to recharge her phone—she was cooking food for her family in the basement. A woman next to her was baking doughnuts on a pan. There was a rumbling noise and right that second the pan with the doughnuts was filled with crumbling plaster. A shell had hit the building above the basement. The woman’s family hadn't had any doughnuts that day. “There wasn't much food. Not everyone had it,” Korchmina says.

To survive, people in the bunker shared with each other.

“We didn’t have diapers, and our neighbors didn’t have food. We used to joke bitterly about trading three diapers for three potatoes. Three diapers meant three quiet nights. Food, clothes, fever syrups, nasal drops, everything changed hands; you couldn't just stand by while a child suffered.”

In March and early April, before shelling and bombing raids began unabated, people made trips from the plant to their homes to bring food. Anna’s 62-year-old father, the only man in her family, got food for all of them. Their apartment burned down, but the barn remained intact for days.

“Rarely did we manage to get out of the basement—during periods of calm. At first you could track them by the clock somehow, usually early in the morning, at five or six, it was quiet. This is when he would run to the barn, to fill a bag with canned food.”

Then the barn next to Korchmina’s apartment was also bombed—but the basement, where the family used to store canned goods, remained.

“The upper shelves were damaged, the lids on the jars flew off, something was boiled. The compote was already cooked—so it boiled over. The condensed milk burned, turned brown, but you could still eat it.”

The problems of ordinary, peaceful life did not disappear in the shelter either: Korchmina had, for example, to figure out how to get her three-year-old daughter to eat. Her shelter neighbor helped her in this—she allowed the girl to feed her cat, Basya, as a reward for breakfast or dinner: “A spoonful of porridge for my daughter, a crumb of food for Basya.”

Besides children, there were many old people in the bunker. Along with Korchmina there was a neighbor from her building. In the past, she worked as a librarian, and then retired, often feeding stray dogs in the yard and giving her daughter Anna candy. She was taken to the bunker with a man who lived nearby. When the shelling began, she “went a little crazy”, Korchmina recalls. The woman could not walk on her own, sometimes going to the toilet under herself while lying on a stretcher. The neighbor who brought her in took care of her: fed her, warmed her, brought her boiling water, took her to the bathroom.

At first, Korchmina recalls, there was a large community living in the air-raid shelter. They cooked for everyone. But when they ran out of food and water stored in the bunker, they divided into small groups in order to get food: it would be very difficult to survive alone. But it was also impossible to feed everyone at once: “We cooked porridge for everyone, and the old ladies would say that the porridge was not so good or that they could not chew it. Not everyone liked the common dish. When we first arrived, we weren’t all hungry right away,” she explains. “We weren't born bums. It was later that we became very much like them.”

The toilets in the bunker were one for everyone—a “big hole”. The first time Korchmina saw it, she didn’t even know how to use it. But after a few days it became clear to her why they made the hole so big.

When the hole under the toilet was filled to the top, the men took shovels and started shoveling it out. They put the contents in sacks and, bombarded by gunfire, began dragging the sacks away from the entrance to the shelter. They had to do it three times in two months. “We all laughed about having to run with these sacks,” Korchmina says. “It’s bad enough, but you don't want that in front of your front door.”

“The inhabitants of Mariupol tried their best to improve life in the bunker,” Korchmina says. “They even set up a smoking lounge in the basement above the shelter. They brought chairs from the plant offices and sat in them, laughing and chatting, as long as there was no shelling.”

One of her neighbors, a young woman, happened to be a hairdresser, so both children and adults in the bunker had their hair cut beautifully. She came to the shelter after a shell hit her building twice, and she only had time to pack the essentials, and all her hairdressing tools were left at home. “But my father ran into her apartment on the way and brought her scissors and a trimmer,” Korchmina says.

“What we couldn’t do was wash properly.” There wasn't even enough water for drinking: “We had a reserve of water in the barn by our house in case of a power outage, to wash our hands and water our flowers. We dragged this water to the shelter. At first we drank it, but when it ran out, we began to collect rainwater. The rain was a blessing. It was dangerous to collect water, but here you have to choose—you either die under a shell or from dehydration.”

But you couldn't do without laundry, especially when Korchmina’s young daughter “had little accidents”. “Sometimes you would wash your hair and then do laundry in this water.”

The water in which the clothes were washed was used again—it was poured into five-liter bottles to wash their hands with it. At first Korchmina was squeamish about the black, dirty soapy water. But after a few days, she stepped out of the darkness of the shelter into the sunlight and saw her hands—ugly, black. “I realized that they were no longer afraid of anything, it wouldn't get any worse,” she says.

“Okay, gotta run, plane is coming”

On April 19th the self-proclaimed DPR announced that it was about to begin taking Azovstal by storm. Ukrainian authorities immediately reported about thousands of civilians in the bomb shelters under the plant. DPR authorities did not wait long to retort that it was a lie. Denis Pushilin, the leader of the unrecognized republic, alleged that the Ukrainian military provided false information concerning the civilians in order to compel Russia to pen a “humanitarian corridor” and to evacuate “mercenaries from various countries” from the plant premises.

“I believe [the Ukrainian military] will always use any forged excuse that can help them survive. A girl, a boy, a wife, a woman, an old lady—this will always be a pretext for them to demand cease of fire and canceling of the storming operation. I think all is being done to achieve this goal,” the DPR “people’s militia” spokesman Eduard Basurin said.

Meanwhile, Azov Regiment published, on April 18th, a video from the bunker beneath Azovstal, in which civilians, mostly women and children, were talking about having lived in the bomb shelter under shelling for several weeks.

It was in this video that Svetlana Kadkalo saw her mother—for the first time in a month and a half. The woman was sitting by the green-coated shelter wall, wearing a plant uniform robe, and swaying back and forth, most likely in pain, her daughter believes. Her mother has spine issues and a serious brain disease, cerebellar atrophy. “She needs painkillers, she needs calcium. She was on therapy, always on pills, wearing spinal support, she had a treatment plan. We helped her walk so that she doesn’t become paralyzed. It cost us a lot of money, and now she has been out of treatment for two months. I have no idea what she will be like when she gets out of there.”

Svetlana lost contact with her mother on March 2th. She fled Mariupol in mid-March when her building was hit by a shell. Kadkalo recalls hearing a bang, pushing the kids from their beds onto the floor and covering them with her own body in a matter of “one second.” “Smoke, dust, darkness. In the morning [I saw] half of the windows missing, our car was like a sieve, the other half of the building destroyed.” Next day, her husband’s parents came out to find a place with mobile signal and were caught in a shelling again. “My mother-in-law was wounded with a splinter, had an open wound, and we decided to take her with us. So two children, my husband, his mother and I, we got into a car and drove for 20 hours from Mariupol to Berdyansk”. It was only on March 17th that Daria, Svetlana’s sister, managed to reach her by phone to say that she was sitting in the Azovstal bomb shelter with their mother, Daria’s husband and their two kids.

Russia’s Deputy Plenipotentiary Representative at the UN Dmitry Polyansky alleged that no civilians could have gone to the plant at their own will: “Civilians could only be brought to that facility as human shields.” Kadkalo’s family—and everyone else Holod has spoken to—had come to the Azovstal bunker because of their fear of shellings: “No one was driving them with a stick. They were just fleeing from those who were destroying our homes.”

Since then, Daria only managed to get outside to call her sister four times. Svetlana Kadkalo recalls that their conversations were short: “We got food, everything’s fine—okay, gotta run, plane is coming.” After a week, there were no more calls from Daria. Svetlana never heard her mother’s voice: she has not come out of the bunker even once, it was too dangerous. “Mom just wouldn’t have been able to run back.” While people who had managed to flee Mariupol were trying to find out whether their family members at Azovstal were alive, the shelter occupants themselves lived in isolation from the outside world. People in one of the bunkers managed to make a radio receiver work.

29-year-old Roman, a Mariupol-based businessman who spent most of March in the shelter with his wife, was not so lucky. He only heard scraps of information on what was going on in the city once every three or four days from service radios of emergency response staff they shared the shelter with.

Some of the emergency response units in Mariupol were “disbanded” in the first days of the war, Roman says, but some personnel remained at Azovstal as volunteers: “They had a fire truck, and they responded to calls. Once there was a rubble by the entrance to a bomb shelter on Azovstal Street [close to the plant], so the boys geared up and went to rescue people,” he recalls.

The rescue team members had radios that they used to contact their colleagues remaining in Mariupol. “Sometimes they would say: ‘A green corridor is open’. We packed in a minute, dropped our bags into a car, and got inside. But before we started, they would say on the radio: ‘Oops, no green corridor, false information.’ We unpacked.”

The most important thing Roman wanted to hear on the emergency response radios was whether he could leave the plant premises without getting into a shelling. While sitting in the shelter, he did not know anything about his parents’ predicament—they stayed in their private house on Kalmius’s left bank, the most dangerous area. “And they were being shelled. Shelled from all directions and sides. I wanted to rescue myself and rescue them. I wasn’t thinking about my country or my city. I did not care much who is going to win at that moment.”

Roman left the plant in late March, before any green corridors materialized. He says that the only food left in his bunker by that time was canned porridge, which they could eat once a day. “Occasionally, we would make soup out of chicken bones. But without power to supply refrigerators, it was all rotten.” Sometimes the military would bring something, but that was not very helpful: “They brought candies for kids, tea, coffee. No real food of any value.”

At first, the military garrisoning the plant would not let him out. Several times, they turned him back, explaining that going to Mariupol was dangerous. However, Roman denies the Russian authorities’ allegations that the garrison was keeping the civilians as “human shields”. “I cannot say they used us to protect themselves. We were told that [they were not letting us out] for our own good: there was active fighting in the city. But [on some days] some people managed to leave. It was never the case that they locked us in and never let anyone out.”

When Roman finally made it to the city in a car belonging to his “shelter mate”, a rescue team member, what he saw through the windshield was “burnt buildings, a broken city.” His apartment was burnt, too. As was a storage building where Roman kept his fish—they ran a family business, salting, drying and selling fish. His parents’ house was hit by a shell but they survived.

Roman left Mariupol and is not planning to come back. “All that is left of my apartment is a frame, and my parents’ house has no roof or walls. Just a heap of bricks scattered around. Typical picture, war photography. I will have to restart my life. This is tough.”

Like death either way

On April 21th, the third day after the storming operation at Azovstal had begun, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin met with the defense minister Sergey Shoigu and ordered him to halt the operation, so that “the lives and health of our soldiers and officers are spared”. Neither Putin nor Shoigu said much about civilians. The defense minister reported that Russia had ceased fire for two hours in two days in a row and prepared buses and ambulance vehicles to evacuate civilians who “might remain” on the plant’s premises. But, according to Shoigu, nobody made use of these humanitarian corridors to leave the plant.

A day later Ukraine’s Vice Prime Minister Irina Vereshchuk stated that Russia had opened a corridor for the garrison to surrender only, and that there still was no corridor for the evacuation of civilians. Russian authorities denied that: Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Maria Zakharova, among others, stated that it was the Ukrainian military who was “not allowing people to leave Azovstal, intimidating and blackmailing them.” On April 25th the Ministry of Defense announced that it was ceasing military action unilaterally and withdrawing troops to a safe distance, “guided by humane principles only.” On the next day, the Azov Regiment reported 35 air strikes by the Russian side just overnight, with some civilian casualties.

Irina Vereshchuk accused Russia of disrupting the humanitarian corridor. “A humanitarian corridor may be opened by an agreement between both parties. A corridor opened unilaterally cannot guarantee safety,” she said and added that no agreement about humanitarian corridors at Azovstal had been reached. Azov Regiment deputy commander Svyatoslav Palamar told the BBC in late April that the civilians hiding in plant bunkers did not believe the Russian side’s announcements of humanitarian corridors. “A couple of days ago, when the Russian troops announced a humanitarian corridor, shelling never stopped,” he said. “And even if people took the risk [then], they would have been under a shelling and they would have been killed for sure.”

Palamar suggested that the civilians’ evacuation from the plant could be guaranteed by third parties, such as the UN, OSCE or the Red Cross. Even the Pope had tried, unsuccessfully, to help rescue the civilians from the bunkers: according to the Italian media, he offered to the Russian authorities to evacuate them by sea on a Vatican ship but Russia declined. On April 26th another attempt to make a deal with Vladimir Putin was made by the UN Secretary-General António Guterres. After the meeting, Guterres’s office made a statement that the Russian president had agreed to the UN’s and the Red Cross’s participation in rescuing the civilians from Azovstal bomb shelters. The Kremlin was quick to deny that: the president’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said that the UN Secretary-General’s proposal would “be considered.”

On April 29th, Andrey Rudenko, a war correspondent for the Russian state-run TV channel VGTRK, published a video in which the Savin family—Natalia, her husband Mikhail and their daughter Elizaveta—talked about their escape from Azovstal. According to them, Azov fighters did not try to stop them: “They said, ‘Well, of course you can evacuate at your own risk. But don’t expect a warm welcome [from the Russians].’”

It was at their own risk, too, that Kristina Dyachuk’s (her last name was changed at her request.—ed. Holod) parents left the Azovstal shelter on 2nd of April. They had gotten there in early March, trying to drive to a safer area in Mariupol. Their car broke right in front of the plant’s gatehouse, and plant employees offered them to wait out the bombings in a bunker.

They made several attempts to leave Azovstal. “But every time our [Ukrainian military] turned them back because of fierce fighting. They would start off but had to go back right away,” Kristina recounts her parents’ story. “My distant relatives’ fourth attempt was a success but they didn’t have space in their cars for my parents.”

Fifth time, Kristina’s parents managed to leave Azovstal on foot. Azov fighters gave them a food reserve. But the bags were so heavy that they had to throw away some cans, Dyachuk says: “Dad has problems with his feet. He even had to throw away his laptop.”

As they were walking toward their house, a shelling began. “There was dirt falling on them so they had to crawl. Crawl on all fours. Dad is 56, and mom is 65.”

The house belonging to Dyachuk’s parents was intact, it was just missing windows blown by a shock wave. They went inside and found that the house was occupied by DPR military. Kristina says that her mother and father shared their house with the soldiers for three days. Then the soldiers left, but two days later Kadyrov’s fighters came—“bearded and barely speaking Russian.”

Kristina’s parents told her that the Russian soldiers shot the fence door lock and then pointed their guns at her father: “Weapons, where are your weapons?”—“What weapons, they’re old people”. Dad said he had a shovel and a crowbar. They searched all of the garages, took all the food they could find and left.” Kristina’s parents stayed in their house for two weeks and then decided to leave Mariupol, for Russia via the DPR. From there, their daughter helped them to go to Spain where she had fled herself soon after the war began. When she saw them at the airport, they looked “thin, exhausted, dehydrated.”

Dyachuk says that for some time, her mother would throw up after eating normal food. She hopes that spending time with their grandchildren will help them restore—Kristina has three kids. “Mom keeps crying. Both of them are saying: ‘We can’t believe we are here, we are all together, and this is over. When we were crawling from the bomb shelter we thought we were not going to make it.’”

Azovstal electrician Andrei Vodovozov with his wife and daughter escaped from the plant on April 4th. Not long before, he claims, Azov Regiment soldiers had set up a firing point in the building next door to the building, under which his bunker was located. Vodovozov decided that since the Ukrainian gun was firing beside him, it meant that the Russian shells would also be coming at him. So he decided to run.

He and his wife discussed this plan with two other families and agreed to leave together. On the morning of April 4th, they woke up, packed their things, and walked across the plant to the central gatehouse, where the Ukrainian military were on duty.

“We said, ‘we're going out’. They said, ‘Where are you going? They'll kill you,’” Vodovozov recalls. The families were told to go back to the shelters. “And for us to go back or to go forward would be like death either way,” Vodovozov says. “Because in order to go back, we had to walk through the open space, I think, the entire plant.” In the end, his family and the other people who had decided to flee took refuge in a military warehouse not far from the gatehouse.

Half a day later, the Vodovozovs met another Ukrainian military man and he helped them get out. He arranged at the checkpoint to let them out and explained which road to take. “At the end he added: ‘Don't you dare get caught by the Russians. If you get caught, they will kill you.’”

“We were in a panic, carrying a bunch of bags, and a baby in our arms,” Vodovozov says. “Tears, screams—but we ran out.” While they ran, it was quiet—no one was shooting.

On their way, the Vodovozovs met some people from Mariupol who had stayed in their houses: they were going to fetch water. People showed them an empty house where they could spend the night: “They said, live there while no one is asking you out, have a rest.”

That same evening Vodovozov saw Russian soldiers in the yard of the house—and ran to them: “I wanted to know whose territory we were on.”

At first the soldiers took aim at him and started “poking me with their guns,” says Vodovozov. Then they found out he was a civilian and answered: “The zone is under Russian control, but sabotage is still possible.” One of the soldiers, according to Vodovozov, gave him a can of stew and a jar of porridge from his personal reserve.

A few days later, Vodovozov’s family was taken to Russia—they were not offered a choice. Like most refugees, they had stomach problems due to poor nutrition. Already in Russia, Vodovozov’s wife went to the hospital to check her health. When she returned, she told her husband that she was pregnant.

Despite the fact that Russian troops had destroyed their city, the Vodovozovs decided to raise their child as a Russian citizen. They themselves had already applied for citizenship. Vodovozov explains that he would not live in the DPR—but, in his opinion, the economic situation in Russia is much better.

“It's going to get worse, and it's not going to end anytime soon”

The organized evacuation of civilians from bomb shelters at Azovstal did not begin until April 30th—two days after Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky met with UN secretary general António Guterres and said he was ready to “immediately” negotiate the rescue of people from Azovstal and implement all agreements—but Russia’s consent was needed. The civilians were removed from the plant with the mediation of the UN and the Red Cross. Some of the people were taken to the territory controlled by the self-proclaimed DPR, while others were taken to the Zaporizhia region of Ukraine.

Svetlana Kadkalo’s family—her sister with her husband, two kids and their unwell mother—left the shelter on April 30th on their own, before any buses came. “The people who were with them [in the shelter] said they lost hope that anyone would ever come for them, and set off on foot while it was quiet,” she says. The [Russian] military took her family to the DPR. Once they are released after the “filtration” procedure (people taken from Mariupol to the DPR territory are not released until their fingerprints and photographs are taken.—ed. Holod), Svetlana’s sister is planning to take their mother to a hospital. Deprived of her medications, she is not doing well after two months in the shelter.

The Russian military evacuated civilians from the basements of houses near Azovstal even earlier in April. They were taken out towards Russia and the DPR. Anna Korchmina was among the evacuees—the exit from her bomb shelter was outside the plant.

Russian soldiers appeared in their bunker on April 24th, Easter. That morning Korchmina and her family and neighbors congratulated each other and baked whatever festive food they could. One man even assembled an oven from bricks to make paski (Ukrainian Easter bread.—ed. Holod). After breakfast, Anna says, there was “a rumor that the military had come.” Soon the inhabitants of the shelter crowded around the Russian soldiers. They were telling them that they would be taking them out.

Before that, the Ukrainian military sometimes came into the bunker—but they did not talk to the residents about evacuation, Korchmina recalls. She didn’t ask them about it, though. She expected to stay in the bunker until the shelling ended and stay in Mariupol. Somewhere in the city her elderly grandmother remained. For two months, while she and her family were hiding in the shelter, nothing was known about her grandmother’s fate: there was no communication and no way to get information. Korchmina wanted to wait until it was safe to go out and find her grandmother. That is why the Korchmins first told the Russian military they would stay in the bunker.

“It wasn’t scary to stay, it was scary to run. By then we knew a lot of cases where you sit-sit-sit, and then you run – and... that's it.” “We had a lot of stuff with us. We dragged it from the apartment to the barn, from the barn to the shelter. The first time we jumped out with everything we had. We sort of settled in the shelter—and then we had to leave everything behind again. To lose everything the second time, that’s how it felt.”

But the servicemen told her that they shouldn’t stay in the shelter: “It will get worse and it will not end soon.”

Anna still knows nothing concrete about her grandmother’s fate. Already out of the shelter, she was able to contact her neighbor. She said that her grandmother’s apartment had burnt down because of the shelling—and she might have been home at the time of the attack.

Civilians were being evacuated from the Azovstal shelters for a week—from April 30th to May 7th. During those days, despite the fact that civilians still remained in bunkers under the plant, there was still fighting on the territory of Azovstal. The parties blamed each other for disrupting the evacuation. On 3rd May, the Azov Regiment commanders said that Russia resumed air and artillery strikes on the plant—and two women were killed under the bombing.

By May 7th, as stated by Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk, all women, children, and the elderly had been removed from Azovstal’s bomb shelters. The deputy commander of the Azov Battalion, Svyatoslav Palamar, however, said afterwards that he could not confirm information that all civilians had been removed—some might remain under the destroyed buildings: “Since no international organization or authority or Ukrainian politician came to Azovstal, there is no special equipment to remove the rubble.”

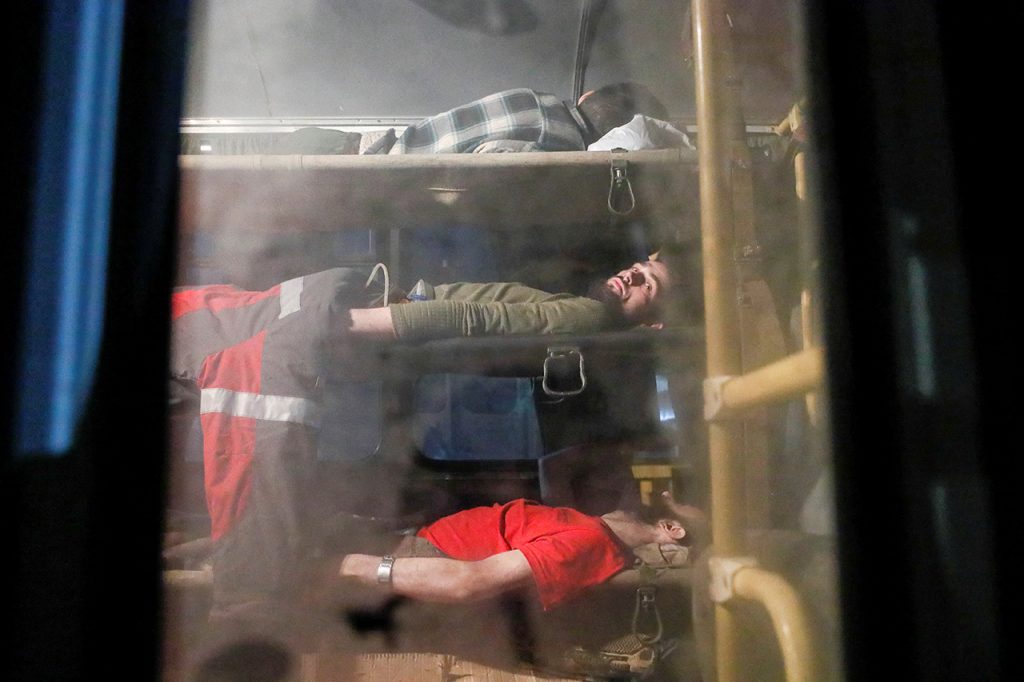

While the civilians were being evacuated, Azov's deputy commander asked Volodymyr Zelensky to also take care of the wounded soldiers at the plant, “who are dying in terrible agony from inadequate treatment”. Ukraine negotiated with Russia to evacuate wounded Mariupol defenders and exchange them for captured Russian soldiers. On the night of 16th–17th May, the general staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine announced that 264 Ukrainian fighters had been evacuated from Azovstal, of whom 53 were seriously wounded. They were all taken to the territory of the unrecognized DPR to be returned to Ukraine under the exchange procedure.

At the same time, the speaker of the Russian State Duma, Vyacheslav Volodin, said that the soldiers evacuated from Azovstal should not be exchanged, but “tried as war criminals”.