Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, world media reported a new wave of human capital flight, or “brain drain”, from Russia. The full number of war-motivated emigrants is unknown, however researchers tally it at around 150 thousand people. While a definitive demographic breakdown of this migration wave is also unavailable, it certainly includes thousands of scientists unable to continue their work in Russia. In this story for Holod, Irina Korneyevskaya researches the fate of scientists who abandoned careers in their homeland, those who stayed in Russia, as well as speculates on the future of Russian science.

“Oh my fucking God, they did it,” were the first words on Patty Gray’s mind, once she heard of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For the 62-year-old anthropologist this was not a mere piece of troubling news. She first visited Russia in 1993, where she studied the privatization of Soviet kolkhozi (were a form of collective farms in the Soviet Union.—ed. Holod), wrote her dissertation on the peoples of the Far North, as well as researched the politicization of the reindeer herders on the Chukotka peninsula.

Although Gray has not visited Russia since 2013 (according to her, it is due to local authorities restricting her research), she has many friends and colleagues remaining within the country. “I thought: ‘Damn, I know so many Russian scientists who are screwed now,’”she remembers. “I know for a fact that they are unhappy with what is going on, so they will either stay in Russia and their lives will become a living hell, or they will be forced to leave the country.”

Gray figured she must help these people acclimatize abroad, especially since most of her present income comes from consulting young scientists on applying for grants and navigating various other academic procedures. “When you are forced to leave your country and loved ones behind, work is the only thing that can keep you going,” she explains. “Even a three-month fellowship at a foreign university can help you collect your thoughts and move on from there.”

When Gray first formulated this idea, there were almost no programs offered to Russian and Belarusian researchers abroad. “I totally get it,” she says. “The primary focus is on those who suffered from Russian military aggression—Ukrainian scientists. ‘Oh, the Russians? Well, if they disagree with the war, they should stay in Russia and fight the regime,’ is an actual opinion I have heard.”

This is not a position that Gray supports. Alongside European colleagues, she attempted to work out the possibilities that were still open for Russian scientists. “We wanted to protest the war and simultaneously support those scientists that are also against it. Some of our colleagues in international organizations believe that all relations with Russia must cease,” Gray says. “While others, myself included, disagree with that approach. We could shut down projects with institutions that support the Russian regime, however, opportunities for individual scientists who renounce the war and hope to further international cooperation should remain. If all connections are severed, Russia will be fully isolated and will be forced to close in on itself.”

“I asked a colleague at a university if they could add Russian scientists to the program they have for Ukrainian scientists,” Gray continues. “He said that his colleagues could not be swayed, although later he texted me: ‘It is really an interesting idea. Nowadays, so many options are open for Ukrainian scientists that most typically ignore our program in search of something more prestigious in the UK or Germany.’ I was relieved—there are enough options for Ukrainian specialists, so I am doing the right thing concentrating on the Russians.”

In the end, Gray was able to discover almost 20 programs that accept Russian scientists’ applications—she published them on her website. Later on, similar lists appeared on some European academic institutions’ websites.

These lists include programs that were initially designated for Ukrainian scientists. “Universities received funding and realized that if they restrict their programs only to Ukrainian applicants, fulfilling the budget will become troublesome,” explains Sonia Plotkina (name altered per her request.—ed. Holod), professor at the Ben-Gurion University in Israel. “Not many Ukrainians have actually come—most men cannot leave, other people stay to help their families. After all, going to some university to do research is not exactly the first thing on the minds of people in their situation. Russian students, candidates and researchers, on the other hand, are precisely the people in need of such opportunities. Over 30 applicants were accepted into our program at Ben-Gurion University, less than third of whom were Ukrainian—the rest were Russian.”

Having researched various opportunities for Russian scientists, Patty Gray contacted the organizers of one such program at the University of New Europe and requested their help in revising the grant applications. Soon she received a message from Anna Serova (name altered per her request.—ed. Holod), who left Russia in early March and was now looking for opportunities to continue her scholarly work abroad.

Danger Surrounds

For Anna Serova, the correspondence with Patty Gray was among the many attempts of reaching out. Settled in one of the post-Soviet countries, the expat would wake at 6am every morning to research programs for scientists, send out emails and prepare her applications. “I studied for my PhD in Europe and was involved in many international activities,” Serova explains. “I reached out to everyone I could remember, including people I only shared a cup of coffee at conferences with. I would explain my situation and ask for their advice on the next steps I should take.”

Serova studies history and anthropology of Soviet mentality, mode of life, and historical culture. In Russia she worked at a state research institution, taught courses, was wrapping up her dissertation and had already planned countrywide scientific expeditions. The 24th of February changed everything. “I conduct historical research and I refuse to work under the ‘Lenin created the Ukraine’ paradigm (Vladimir Putin posited it in his address to the nation on Feb. 22nd.—ed. Holod),” says the researcher. “Once it got to the point where I could not eat or sleep for a full week, I realized it was time to leave.” Together with her husband and two children, Serova headed for Armenia. Her research plans had to be broken, and in June she officially resigned her position at the institution where she worked.

During her expeditions, Serova conducted many in-depth interviews with various inhabitants of Russia, so the roaring support for the war in Ukraine did not come as a surprise to her. “I am aware that the president’s vision is shared by a very large group of Russians,” she says. “I realized that many of the results of my research make me severely depressed. Looking into the abyss is scary. I tried to find out how my respondents remembered the USSR. It is always a nostalgia for brutal force, so the war-induced euphoria we see nowadays is not at all surprising.”

This did not make matters better, however. “The first few weeks [following departure] were shrouded by the sense of utter confusion,” Serova remembers. “It is a difficult situation to be in, when you yearn for something, but have no idea what it is; or what you are supposed to want. People in our culture typically do not apply for 15 different programs at once—we usually single out one place to focus on and if we get rejected, only then do we move to other options. For Western academia, however, it is completely normal for candidates to send out hundreds of applications and get only one positive response.”

According to Serova, Patty Gray was of great help to her in getting accustomed to this new paradigm. Gray was, in essence, her advisor in the application process (although the American modestly claims to have only ‘held Anna’s hand through this’). In the end, one of the many emails yielded the desired result: Serova was accepted into a three month program at a university in the Middle East. Currently, Serova is finishing up her book on post-Soviet countrysides, which she started writing before the war started.

“I never planned on leaving Russia, because I am a patriot—in the normal sense of the word, that is—and I am sure I could have done a lot of good for my country,” she says. “Although, I realize that the impact I have is literally ‘on paper,’ I am certain that sociological research is vital in transforming Russia.” Nevertheless, Serova became aware of the fact that her work might one day serve as ground for governmental persecution, once the legal trial of the Memorial society was initiated. “My colleagues and I never thought that studying the Soviet grassroots resistance movements (and those in the 1990s) could land us on any political plain today—it appears we were wrong,” the scientist says. “I suddenly felt the need to be cautious in what I write; sensed an imperceptible threat. Similar to walking alone at night, there is a sense of surrounding danger. In fact, this is an apt metaphor for what has been going on the last three months—complete and utter darkness.”

Patty Gray also errs on the side of caution. “There are people I wanted to help, but decided to not endanger them with a communication from an American,” she explains. “If they reach out first, I will gladly respond. It must sound silly, but I fear even sending emails to those still in Russia. It breaks my heart that my presence in their life may put them in grave danger.” Of the scientists that Holod interviewed, only one did not request anonymity.

Anna Serova’s family has already made plans for when her fellowship comes to its end: they are moving to a European country—a local university offered her a spot in a year-long program. What comes next is yet undetermined, which is the scary part. “Our financial state in Russia was more or less predictable,” Serova explains. “And now it is, as my husband calls it, like a ‘gypsy science’. I will have work over the coming year, but no one knows what will happen next. There are fairly stable positions in Europe, but they are scarce.” Other respondents agree: the constant semi-aimless search for new grants and academic positions is tiresome and at some point one yearns for some stability.

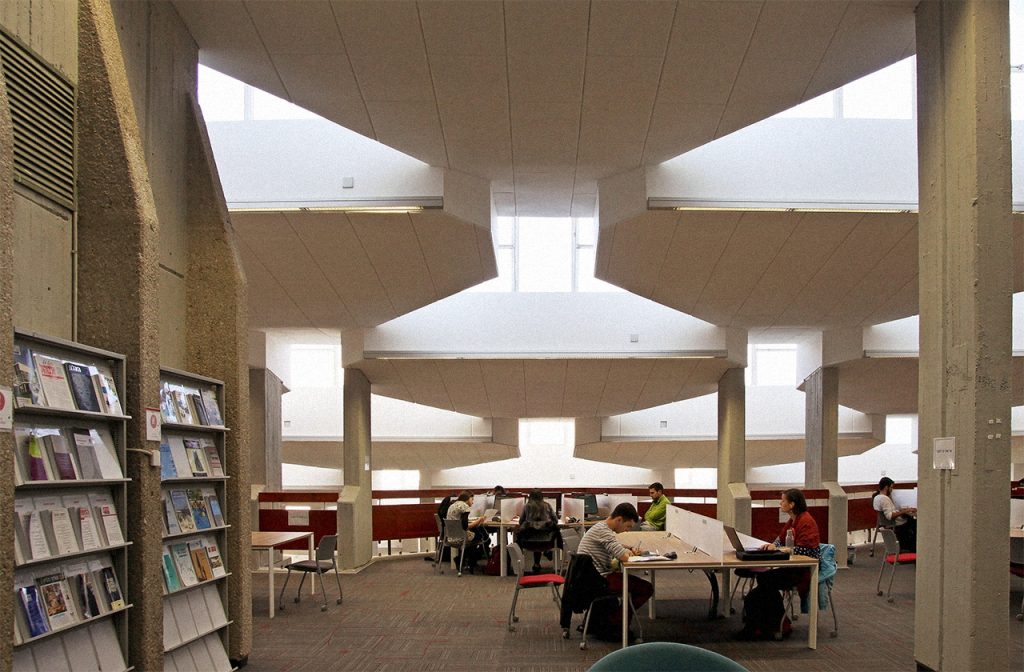

Paradoxically, the situation is the most dire for the most distinguished specialists who want to leave Russia, professor Plotkina explains. “5 years after receiving a PhD is the postdoctorate period. Researchers at this stage in their career have a great many resources and opportunities to fit in somewhere without becoming a refugee,” Plotkina says. “The academicians who received their PhDs 10 years ago or more and held stable positions are in a much more complicated situation. Global employment in humanities and social sciences is becoming more and more scarce every year, the competition is beyond stiff, and the market is flooded with native candidates, who bring their knowledge of language, understanding of the local system, and, of course, connections. The latter is very important in academia. That is how informal knowledge is transmitted, such as: unadvertised open positions, the kinds of specialist that are sought after, successful ways to compose application emails. Sometimes I receive CVs from such serious professionals that my jaw drops.”

According to Plotkina, the Ben-Gurion University is currently figuring out the right allocation for the academic resource that suddenly appeared this year. “We have a network of researchers who study Russia and Eastern Europe broadly—and we suddenly became somewhat of a vocational committee for refugee academicians,” she continues. “This is a historical moment and we are working on finding sponsors to create a hub for those that left their homelands and are now in Israel. We even held an informal meet-and-greet for those who came from Russia on a rooftop in Tel Aviv—there were around 30 people, all professionals in different areas and most of them utterly lost.”

Psychological Isolation

Patty Gray, who used to study the Chukotka peninsula, recounts that after the USSR collapsed, European anthropologists put significant effort into unifying the local studies of the Arctic into a single discipline. “Now we are coming back to square one, — says Gray. — I have been doing scientific work for 30 years and, apparently, in that time Russia went from being closed to opening up to international scientific cooperation and now it is closing up again. It is absolutely heart wrenching.”

Simultaneously, even in the months leading up to the beginning of the war, the Russian Ministry of Education and Science was constantly incentivizing scientists to participate in global collaboration. In 2012, the agency launched ‘Project 5-100’: the aim of this initiative was to aid ‘at least 5’ Russian universities in placing in the top 100 universities in the world rating. No money was spared and universities reported their faculty’s increased publication rate in global scientific journals. The program was not implemented smoothly, however, as many universities would artificially inflate their statistics in order to get more funding; these institutions would bribe unscrupulous publications, whereas on their reports would cite “high acceptance rates”. That, however, did not affect the government’s goals: in a campaign called ‘Priority-2030,’ published in 2021, the Ministry of Education and Science retained the aim to promote Russian academia on the world stage and the publications in foreign journals remained a key indicator of success.

“Over the past year with the aid of the Ministry of Education and Science, our institute consistently received offers for international partnerships, for instance, Russian and German scientific foundations offered funding to create joint programs for Russian and German academic institutions, — says Anna Serova. — This was ubiquitous. That way, those who wished to become part of the international scientific community, had the opportunity to do so. Now, it seems, it has become impossible.”

According to Serova, many of her colleagues remain in Russia for different reasons. “All scientists have the same source of income — government funding, — she explains. — Hence, leaving would mean losing everything. Only a few are willing to make this sacrifice.”

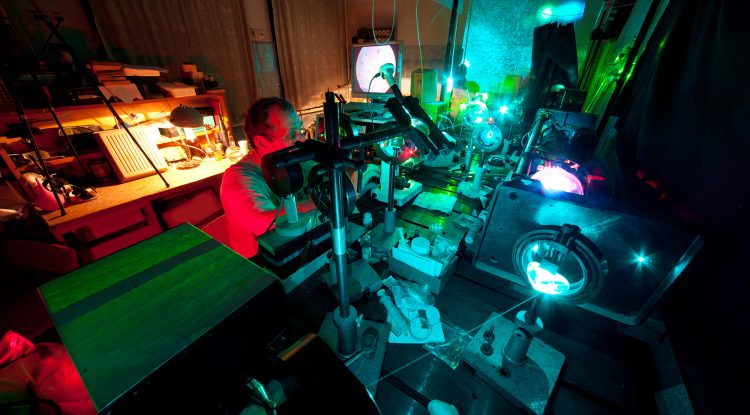

“Once providing for my family and doing what I love becomes impossible in Russia, I will, probably, consider leaving the country, — says a 33-year chemistry PhD candidate Valentin Ivanov (name altered per his request — ed. Holod). — Hopefully, it will not come to it.” Ivanov heads a laboratory at a university in the Ural region. Under his supervision, a team of seven scientists are developing a project for creating supramolecular structures. “I have a team and it constantly grows, — says Valentin. — I cannot simply tell them: go on without me — and leave.”

Ivanov’s team actively collaborates with Russian colleagues in other cities and still keeps in contact with a group of French scientists. “We maintain friendly relations. Naturally, all of us agree that violence and aggression are never justified, — says Ivanov. — We decided that we should keep doing what we do best — science. And we will keep at it, no matter the scale of the shitshow around us.”

Contacts with other foreign colleagues seems to have been severed. “We were nearing an agreement on a collaborative project with a group of Austrian scientists. In light of recent events, however, our communication has been put on pause. I have no idea what we can offer them now. — the scientist explains. — What could be attractive about the idea of collaborating with Russians? We were set to have a conversation over the phone in April, but there has been no communication from their side and I did not reach out either, because I understand why they didn't. I could text or call them and they would basically tell me that a decision has been made to not have any official relations with Russia — why would I want to hear that? I would much rather keep our relationship on pause than ruin it completely.” In Ivanov’s own words, after February 24th he started feeling a ‘psychological isolation’ from the global scientific community: “It’s not because we, Russians, were ostracized, it is because we personally feel uncomfortable with what is going on.”

The Ministry’s statements from the past few months seemed to have omitted the goal of integrating Russian science in the global scientific community: in response to some European nations halting their partnerships with Russia in fields of science and education, Russian officials announced the country’s withdrawal from the Bologna Process, the education system of Europe and the US. After the ‘Web of Science’, largest scientific database, restricted its access to Russian users, the Ministry proposed to lift the requirement for scientific publications on this, as well as on other foreign databases, although since 2012 that was the most important metric for receiving grants and other funding from the government. Currently, the second largest scientific database, Scopus, is still available in Russia, however, Holod’s respondents are counting days to its potential withdrawal from the country.

“The Ministry of Education and Science is so quick in changing its mind because they have no understanding of how education and science work. — says a Russian sociologist (name omitted per request — ed. Holod). — Modern science cannot thrive in isolation from the world. Science in and of itself is a global exchange of knowledge. Bureaucrats have never attributed real value to scientific achievement, the substance of such work is beyond them. When they needed a boost in citations of Russian works in international publications, they were not interested in the quality of these works — they just needed numbers. This attitude prevails nowadays and I would not be surprised if they ran the Russian scientific enterprise to the ground. After all, why not, they could not care less.”

According to the Valentin Ivanov, his laboratory received communications which urged the team to disregard the international publication metric. “These attempts at flexing muscles and pretending that our science will flourish in isolation from the rest of the world is laughable, — Ivanov argues. — Any scientist’s work boils down to a publication. It gets published in a scientific journal and other scientists peer-review it. The better the journal, the better are the peer reviewers. What determines the importance of these scientists is the amount of their publications and how often they are cited by other researchers. If your work gets cited, that means you are an important scientist.” At least according to Holod’s respondents, no international journal as of yet has rejected a publication solely based on the author’s Russian nationality.

The halt on the import of supplies for experiments is another destructive effect of the war on the sciences. Valentin Ivanov’s lab is already unable to acquire the necessary chemical reagents. “[The supplier] informed us that, in light of the situation at hand, some of the line items on our order will not be fulfilled, — the scientist reports. — They were the items I had planned on utilizing to report to the government on the allocation of their grant money. As a result, we will not get to complete our work as planned. I guess we will have to ask our colleagues for help or maybe synthesize some reagents ourselves if we are able to.” Updating the equipment is also up in the air: “We wanted to get a fluorescent microscope. Nikon and European brands do not deliver to Russia anymore, — Ivanov continues. — And the prices of alternatives that are still on the market skyrocketed. For instance, a Leica microscope used to cost a million rubles, now it is priced at two million. The way it stands, we are going to have to fix up the equipment that we currently own and it will cost us about the same as we would normally spend on a new microscope.”

According to Ivanov and his colleagues, the biggest fear that all Russian scientists who stayed in the country share is the uncertainty of the future. “Official sources claim that nothing is changing, but you can see change with your own eyes. — Ivanov claims. — And the more they try to calm you down, the more tense you get. You have no idea what life will look like over time. It is very challenging to do science without a firm plan — you fully rely on funding at the very least. We formulate projects, apply for grants and never know what the money we receive will actually cover. Moreover, science is the pursuit of the truth. We do what we do, so that humanity can better understand the world it lives in and create useful technology. And the back-and-forth between the scientists and society is vital in keeping the scientists’ bearings. When this communication breaks, you lose grasp of the society you are living in. It is psychologically important to have purpose in your work and it is hard to keep going when that is lost. Is our only purpose developing yet another missile?”

You Only Live Once

In October of 2021, Alyona Syutkina, a 26-year old graduate of the Perm pharmaceutical academy, presented her dissertation and was accepted into a six month fellowship in Germany through the DAAD grant. The German laboratories profoundly impressed her: “The day I arrived in Germany I asked myself: we have so many good people and natural resources in Russia, but why is our quality of life so low? Why do we have so little prospects? I admire Russian scientists, for they are still working against all odds.” — says Syutkina. In fact she had planned to return to Russia in April to continue her work there. But that was prior February 24th.

“When the war started, I instantly took my outrage to social media and then new horrifying laws started being implemented in my homeland. — says Syutkina. — My German colleagues were persuading me to not go back. They were afraid for my safety.” Her colleagues in Perm were of the same opinion: “They realize that, technically, you could do fine in Russia if you just keep your mouth shut. They were more worried about my career prospects, — Alyona continues. — My supervisor told me: ‘We will keep working until we can’t. Then we will figure something out.’ They always do.” Syutkina is of the opinion that the funding of most scientific work in Russia will be inevitably cut, and “priority will be given to projects that can instantly start mass production.” One of the reasons she decided to stay in Germany was her fear that working in Russia she will not be able to financially provide for her family; her father is the only one employed (as a driver) in their whole family, while Alyona’s mom stays at home, raising three small children.

Having decided not to return to Russia, Alyona Syutkina asked her German supervisor if she could continue her work at the lab after the current program ends. Her colleagues supported her, however, she was not granted a paid position at this university. “My supervisor needs to receive grant money to pay his subordinates their salaries. He already has two employees and no spot for a third one,” — Syutkina explains. She got admitted to the same university as a student and continued her work at the lab without any funding; all so that she could keep doing what she loves as well as look for new opportunities. Currently, Syutkina is researching programs for scientists from Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia.

One day a colleague of Syutkina’s reached out with an opportunity to do temporary postdoctoral work with her friend, a professor in Finland. “We got in contact, he interviewed me and said: ‘I want you to work with me, so we will go ahead with the paperwork, which should take a few weeks.’” Two weeks later, the professor reached back out to her with bad news: the admissions office did not accept her candidacy. “I cannot say for certain, however, it seems I was rejected because of my Russian nationality. — says Alyona, who has resumed her search for other opportunities in Europe. — The admissions department did not provide any formal reason for my rejection, which is why I think it must have something to do with my citizenship.” The professor at the Ben-Gurion University, Sonya Plotkina, also says that their new program has temporarily stopped accepting Russian applicants: “I am assuming, it does not look good on paper that most of the funding goes to Russians.”

“We are not suffering. Russia is still full of great people to work with who share our views, goals and ambitions, — Valentin Ivanov posits. — Guys like me, 30-40 year-olds, have the greatest concerns. We think we might be nearing the apex of our careers. You only live once. When you are 70 or 80, no one will thank you for sitting at your dull table at your dull laboratory. The more our reality restricts us from doing what we love, the more of us start wondering what they are even doing here. And when they realize that there is no answer to this question — they leave.”